If you were a white boy in the suburbs of Cape Town during the heyday of apartheid in the early 1970s, you didn’t know any black people. Not only socially, but even as public figures. That was the whole idea: Apartheid laws meant your school was all white, your suburb was all white (and any black person found there after dark who wasn’t a live-in domestic worker faced summary arrest), your media was all white and told stories only about white people — you were sometimes privy to a bit of a debate about apartheid, but it was conducted exclusively among white people, sometimes around a dinner table where it would be suddenly paused whenever “the maid” walked in bearing another course.

Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and scores of others languished literally on our horizon, Robben Island scarcely visible as you watched the sun set from Milnerton Beach, but you never heard anything about them — I was at university before I even knew who Nelson Mandela was, and I had been a comparatively politically aware adolescent: The media white-out was total.

There were black people all around us, of course. They bore only first names, and they existed only to make our lives more comfortable, cooking, cleaning, doing the garden, working for our parents. Of course there were cool black people elsewhere — Pele and Muhammad Ali, Jimi Hendrix and Sir Garfield Sobers, Link from “Mod Squad” and others — but not in South Africa.

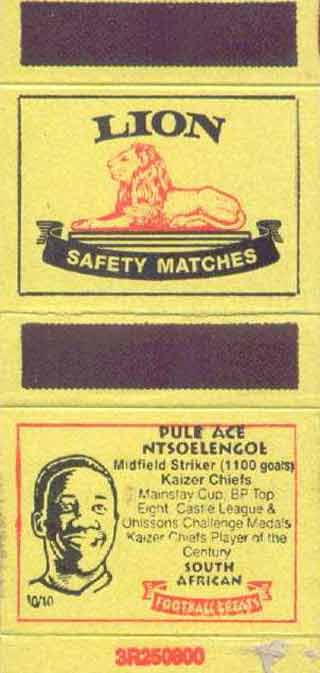

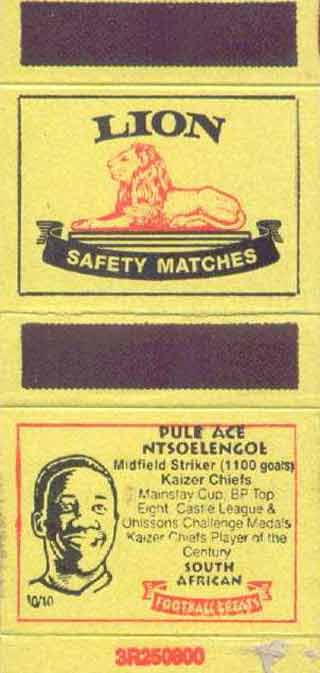

At least, not before Ace Ntsoelengoe, the Kaizer Chiefs attacking midfielder, and his partner in crime, the nimble winger Teenage Dladla — and of course the two great midfield schemers of Soweto in the mid 1970s, Jomo Sono and Computer Lamolo. Wagga-wagga Likoebe, and Chiefs’ legendary Malawian ‘keeper Patson Banda. And a handful of others. The first black people whose full names many of us ever learned (okay, Ace’s real name was Pule, and Teenage’s was Nelson, but their soccer monikers were not English names chosen because their given names were unpronouncable by white people)

Although it frowned upon a game that the likes of Pele, Eusebio, Jairzinho and Garrincha had long ago proved made nonsense of any white supremacist pretenses, the apartheid system nonetheless had its own soccer leagues: A white league in which every Friday night, the likes of Cape Town City and Hellenic would take on Arcadia Shepherds, Durban City (the club that eventually nurtured Liverpool’s own Bruce Grobelaar!) and Highlands Park. Of course the crowds at these games, and those of us who played soccer on the school playground (it was officially discouraged; the only winter games our schools officially sanctioned were rugby and field hockey)were from the politically unreliable (from the regime’s perspective) segments of white society — Brits, Jews, Greeks and Portuguese.

But by around 1974, the regime had heard its death knell tolling in the distance, as the coup in Portugal ended a half century of fascism, and with it the colonial regimes in Mozambique and Angola. White Rhodesia was looking increasingly vulnerable as the Zimbabwean liberation movement picked up its guerrilla campaign. At home, black students were starting to organize themselves and the trade union movement had survived its baptism of fire in the massive Durban strikes of the previous year. One area the regime decided it could afford to experiment was sport, and it began allowing, initially, white and black “national” teams to play against each other, and then eventually the leading white clubs to play against the leading black clubs.

Although Chiefs stuttered the first time, they soon made the Mainstay Cup tie their own, and Ace Ntsoelengoe — who could do things with the ball none of us had ever seen before, score thirty yard screamers, lobs and curlers from tight angles, or waltz through a defense with the ball glued to his foot before strolling it into an empty net, was the player you wanted to be.

In one of the more bizarre and largely unnoticed moments in the annals of international football, Argentina in 1976 sent their national squad — under the banner of an “Invitation XI” to beat the Fifa ban which at that stage prevented teams, but not individuals, from playing in South Africa — that was how I got to see Kevin Keegan and Mick Channon turn out for Cape Town City in 1978. They played against South Africa’s first ever “Multiracial” national team, turned out in Springbok green, with equal (rather than proportional) representation of white, coloured and African players. (These days, curiously enough, a national team selected purely on merit would have six or seven Coloured players — not bad for a minority that comprises significantly less than 10 percent of the population, but again, that’s another story.)

It was to be Ace’s only opportunity to represent his country, or at least his idea of what his country should be, and he revelled in it. The Argentines may have won the World Cup two years later, but they were hammered 5-1 in South Africa — and four of those goals were scored by Ace.

He played abroad, of course, many many seasons with the Minnesota Kicks in the now defunct North American Soccer League. In those days, there were no African players in any of the European leagues — hardly any European players played outside their home countries until some time in the 1980s, and even then it was initially mostly a case of a handful of galacticos playing in Italy. I won’t make extravagant claims for what Ace might have achieved in Europe, but I suspect he’d have been magic.

Another goal for the Minnesota Kicks

But Ace was a double victim of apartheid: He was oppressed as a black person with no rights, living the same reality those ruled by far-off European countries in the colonial era — except that the rulers were a stone’s throw away. Black people were effectively excluded from all power, and forced to contend with a legal structure that deemed them fit to live in the white-dominated urban space only to the extent that they were able to serve the needs of white people. And when they challenged those power arrangements, they were viciously suppressed — most graphically during the Soweto uprising of 1976.

The lifeless body of 13-year-old Hector Petersen, the first of many Sowetans shot dead by police, is carried away on June 16, 1976

Ace and his fellow soccer stars were part of a people struggling against vicious odds to be free. And he paid a price for that struggle, in that the FIFA ban — necessary to help isolate the apartheid regime — also meant that he would never get the opportunity to shine on the international stage as every coach, player and pundit in South Africa knew he would if given the chance.

Ace was not a political activist, yet by his very existence as an icon of a new form of urban African existence, he was innately subversive to the apartheid order. If the apartheid idea was that black people would not have any presence or identity in the city except to work for white people, then the emergence of Ace and his contemporaries as the first generation of urban black celebrities in South Africa (recognizable across social boundaries), using their skills and talents to enrich themselves or (more likely) black club owners was a negation of the very basis of apartheid’s version of black identity as a rural, tribal phenomenon.

Ace and his contemporaries were hip and styling, and their game spoke of an attitude of freedom, creativity and power. Whether intending to or not, they were social role models for thousands of city-born black kids who took their destiny into their own hands starting with the 1976 uprising.

The regime may have hoped that allowing black soccer to flourish was a “safety valve,” but instead it helped cultivate the urban black civil society that tilted decisively, and across all classes, to the liberation movement. I’ll never forget the adrenalin rush I felt in 1988, watching the Mainstay Cup Final on television. It was the height of the State of Emergency, and all open political activity had been crushed. Many of my closest friends and comrades were in prison or had been forced into exile, I was living in hiding and had mentally compiled an extensive reading list that I hoped would help wile away the years I was expecting to spend behind bars. It was a dark and gloomy time, and liberation seemed decades away, along a road that involved much pain and suffering.

And yet here, on live television with a crowd of around 50,000 turned out to watch Chiefs and Swallows (if I remember correctly), the head of the football federation was making a speech setting out the democratic demands of the movement, the black-green-and-gold flag of the ANC was fluttering in the bright sunshine even though flying it carried a prison sentence, and the tears rolled freely down my cheeks as the crowd rose, fists in the air to sing our national anthem, Nkosi Sikelel i’Afrika. I knew in that moment that the regime had lost. Whatever it did to the activists of the political movement, the regime could not reverse the gains we had made in civil society. Maybe it wasn’t going to be decades, after all. And it was obvious not only in the flags and songs: As I remember it, that day the Chiefs lineup included Gary Bailey in goals, Jimmy “Brixton Tower” Joubert at the heart of defense and Neil Tovey in the midfield, while Swallows included striker Noel Cousins — all talented white boys who were now playing for Soweto clubs. Here was the future which Ace, in his unassuming way, had helped inaugurate.

While Jomo Sono may have gone on to manage the national team and create a franchise out of himself and his team, Ace was all quiet grace, letting his game do the talking. He was, in every sense, a natural, and spent the post apartheid years of his retirement coaching the next generation at Chiefs.

And so, a little weepy, here in Brooklyn New York, I’ll put some old Soul Brothers in the i-Pod, and think about what might have been, and what was. Hamba Kahle, Ace, as we used to say in farewell to the comrades slain by the regime, those who would never see the freedom for which they gave their lives. Go safely. You scored some memorable goals, but none more so than the freedom and dignity of your people — all of us.

.jpg)