If you were a white boy in the suburbs of Cape Town during the heyday of apartheid in the early 1970s, you didn’t know any black people. Not only socially, but even as public figures. That was the whole idea: Apartheid laws meant your school was all white, your suburb was all white (and any black person found there after dark who wasn’t a live-in domestic worker faced summary arrest), your media was all white and told stories only about white people — you were sometimes privy to a bit of a debate about apartheid, but it was conducted exclusively among white people, sometimes around a dinner table where it would be suddenly paused whenever “the maid” walked in bearing another course.

Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and scores of others languished literally on our horizon, Robben Island scarcely visible as you watched the sun set from Milnerton Beach, but you never heard anything about them — I was at university before I even knew who Nelson Mandela was, and I had been a comparatively politically aware adolescent: The media white-out was total.

There were black people all around us, of course. They bore only first names, and they existed only to make our lives more comfortable, cooking, cleaning, doing the garden, working for our parents. Of course there were cool black people elsewhere — Pele and Muhammad Ali, Jimi Hendrix and Sir Garfield Sobers, Link from “Mod Squad” and others — but not in South Africa.

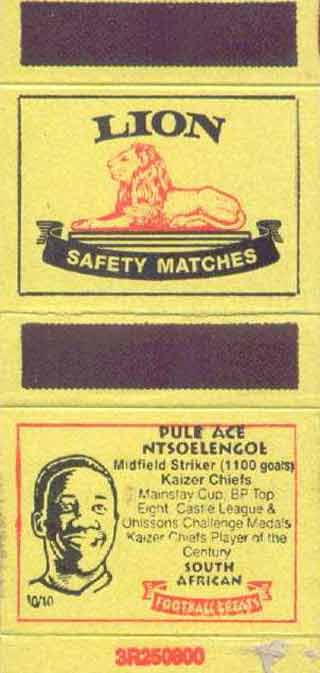

At least, not before Ace Ntsoelengoe, the Kaizer Chiefs attacking midfielder, and his partner in crime, the nimble winger Teenage Dladla — and of course the two great midfield schemers of Soweto in the mid 1970s, Jomo Sono and Computer Lamolo. Wagga-wagga Likoebe, and Chiefs’ legendary Malawian ‘keeper Patson Banda. And a handful of others. The first black people whose full names many of us ever learned (okay, Ace’s real name was Pule, and Teenage’s was Nelson, but their soccer monikers were not English names chosen because their given names were unpronouncable by white people)

Although it frowned upon a game that the likes of Pele, Eusebio, Jairzinho and Garrincha had long ago proved made nonsense of any white supremacist pretenses, the apartheid system nonetheless had its own soccer leagues: A white league in which every Friday night, the likes of Cape Town City and Hellenic would take on Arcadia Shepherds, Durban City (the club that eventually nurtured Liverpool’s own Bruce Grobelaar!) and Highlands Park. Of course the crowds at these games, and those of us who played soccer on the school playground (it was officially discouraged; the only winter games our schools officially sanctioned were rugby and field hockey)were from the politically unreliable (from the regime’s perspective) segments of white society — Brits, Jews, Greeks and Portuguese.

But by around 1974, the regime had heard its death knell tolling in the distance, as the coup in Portugal ended a half century of fascism, and with it the colonial regimes in Mozambique and Angola. White Rhodesia was looking increasingly vulnerable as the Zimbabwean liberation movement picked up its guerrilla campaign. At home, black students were starting to organize themselves and the trade union movement had survived its baptism of fire in the massive Durban strikes of the previous year. One area the regime decided it could afford to experiment was sport, and it began allowing, initially, white and black “national” teams to play against each other, and then eventually the leading white clubs to play against the leading black clubs.

Although Chiefs stuttered the first time, they soon made the Mainstay Cup tie their own, and Ace Ntsoelengoe — who could do things with the ball none of us had ever seen before, score thirty yard screamers, lobs and curlers from tight angles, or waltz through a defense with the ball glued to his foot before strolling it into an empty net, was the player you wanted to be.

In one of the more bizarre and largely unnoticed moments in the annals of international football, Argentina in 1976 sent their national squad — under the banner of an “Invitation XI” to beat the Fifa ban which at that stage prevented teams, but not individuals, from playing in South Africa — that was how I got to see Kevin Keegan and Mick Channon turn out for Cape Town City in 1978. They played against South Africa’s first ever “Multiracial” national team, turned out in Springbok green, with equal (rather than proportional) representation of white, coloured and African players. (These days, curiously enough, a national team selected purely on merit would have six or seven Coloured players — not bad for a minority that comprises significantly less than 10 percent of the population, but again, that’s another story.)

It was to be Ace’s only opportunity to represent his country, or at least his idea of what his country should be, and he revelled in it. The Argentines may have won the World Cup two years later, but they were hammered 5-1 in South Africa — and four of those goals were scored by Ace.

He played abroad, of course, many many seasons with the Minnesota Kicks in the now defunct North American Soccer League. In those days, there were no African players in any of the European leagues — hardly any European players played outside their home countries until some time in the 1980s, and even then it was initially mostly a case of a handful of galacticos playing in Italy. I won’t make extravagant claims for what Ace might have achieved in Europe, but I suspect he’d have been magic.

Another goal for the Minnesota Kicks

But Ace was a double victim of apartheid: He was oppressed as a black person with no rights, living the same reality those ruled by far-off European countries in the colonial era — except that the rulers were a stone’s throw away. Black people were effectively excluded from all power, and forced to contend with a legal structure that deemed them fit to live in the white-dominated urban space only to the extent that they were able to serve the needs of white people. And when they challenged those power arrangements, they were viciously suppressed — most graphically during the Soweto uprising of 1976.

The lifeless body of 13-year-old Hector Petersen, the first of many Sowetans shot dead by police, is carried away on June 16, 1976

Ace and his fellow soccer stars were part of a people struggling against vicious odds to be free. And he paid a price for that struggle, in that the FIFA ban — necessary to help isolate the apartheid regime — also meant that he would never get the opportunity to shine on the international stage as every coach, player and pundit in South Africa knew he would if given the chance.

Ace was not a political activist, yet by his very existence as an icon of a new form of urban African existence, he was innately subversive to the apartheid order. If the apartheid idea was that black people would not have any presence or identity in the city except to work for white people, then the emergence of Ace and his contemporaries as the first generation of urban black celebrities in South Africa (recognizable across social boundaries), using their skills and talents to enrich themselves or (more likely) black club owners was a negation of the very basis of apartheid’s version of black identity as a rural, tribal phenomenon.

Ace and his contemporaries were hip and styling, and their game spoke of an attitude of freedom, creativity and power. Whether intending to or not, they were social role models for thousands of city-born black kids who took their destiny into their own hands starting with the 1976 uprising.

The regime may have hoped that allowing black soccer to flourish was a “safety valve,” but instead it helped cultivate the urban black civil society that tilted decisively, and across all classes, to the liberation movement. I’ll never forget the adrenalin rush I felt in 1988, watching the Mainstay Cup Final on television. It was the height of the State of Emergency, and all open political activity had been crushed. Many of my closest friends and comrades were in prison or had been forced into exile, I was living in hiding and had mentally compiled an extensive reading list that I hoped would help wile away the years I was expecting to spend behind bars. It was a dark and gloomy time, and liberation seemed decades away, along a road that involved much pain and suffering.

And yet here, on live television with a crowd of around 50,000 turned out to watch Chiefs and Swallows (if I remember correctly), the head of the football federation was making a speech setting out the democratic demands of the movement, the black-green-and-gold flag of the ANC was fluttering in the bright sunshine even though flying it carried a prison sentence, and the tears rolled freely down my cheeks as the crowd rose, fists in the air to sing our national anthem, Nkosi Sikelel i’Afrika. I knew in that moment that the regime had lost. Whatever it did to the activists of the political movement, the regime could not reverse the gains we had made in civil society. Maybe it wasn’t going to be decades, after all. And it was obvious not only in the flags and songs: As I remember it, that day the Chiefs lineup included Gary Bailey in goals, Jimmy “Brixton Tower” Joubert at the heart of defense and Neil Tovey in the midfield, while Swallows included striker Noel Cousins — all talented white boys who were now playing for Soweto clubs. Here was the future which Ace, in his unassuming way, had helped inaugurate.

While Jomo Sono may have gone on to manage the national team and create a franchise out of himself and his team, Ace was all quiet grace, letting his game do the talking. He was, in every sense, a natural, and spent the post apartheid years of his retirement coaching the next generation at Chiefs.

And so, a little weepy, here in Brooklyn New York, I’ll put some old Soul Brothers in the i-Pod, and think about what might have been, and what was. Hamba Kahle, Ace, as we used to say in farewell to the comrades slain by the regime, those who would never see the freedom for which they gave their lives. Go safely. You scored some memorable goals, but none more so than the freedom and dignity of your people — all of us.

Great piece. Plus, from a personal perspective that fact that Argentina was the first team to play a multiracial ZA side is really touching.

Very nice: stumbled on this after having had a chat the other night about goalkeepers, and who were the best I’d ever seen – so we got into Buffon vs. Julio Cesar, and then I remembered a name from my youth in South Africa – Patson Banda who, infuriatingly, does not even have a wikipedia entry! Perhaps you would do so because Banda was one of the best I’ve ever seen, another wasted talent: I remember reading a small piece about the philosopher Walter Benjamin, and someone once saying that the Nazis’ greatest sin was in his death: I know, one in 80 million, but a face – and a destiny broken – by a system sometimes just makes that system not only evil – but APPEAR evil.

Anyway, I’ve spouted enough but could I ask whether you know whatever happened to Banda? I would be love to know: I was a white boy going to Sacred Heart College at the time (so we were integrated, hence why I knew about the great Banda and his exploits!) and fashioned myself the same wardrobe in my budding goalkeeping youth … memories, though I dare say mine are tinged slightly differently than yours.

Many thanks for the trip down memory lane anyway!

Pingback: The Global Game | History | Soccer fields, for King and Atlanta, lent space to move ‘beyond Vietnam’

Stumbled upon this only today. Having grown up in a South African township during these years, for me it’s just one of those things. Patson Banda is South African not Malawian and he turned out for Orlando Pirates not Kaizer Chiefs.

Alex NY, Patson “Sparks” Banda is now a soccer pundit on SABC (sometimes).

ace was the most hublest down to earth person you could find. a far beter player than jomo no offence.sad that he had to leave this earth in such a way. he was a silent assasin on the playing field, a master indeed.

ace was the most humblest of persons you could find, on and off the field of play.also no offence,to me and many others ace was the far better player than jomo.sad that he had to leave this earth in this way but he was indeed a master and a silent assasin on the playing field.

Anyway, I’ve spouted enough but could I ask whether you know whatever happened to Banda? I would be love to know: I was a white boy going to Sacred Heart College at the time (so we were integrated, hence why I knew about the great Banda and his exploits!) and fashioned myself the same wardrobe in my budding goalkeeping youth … memories, though I dare say mine are tinged slightly differently than yours.

Great piece. Plus, from a personal perspective that fact that Argentina was the first team to play a multiracial ZA side is really touching.

Nice of this Tony Karon.

Interesting!I love this kind of information.These is very fascinating information – from afar! Thanks

weber natural gas grill

Hi, real appreciation for the great article and the information, it is really good and helpful.Thankyoumichael kors watches blackfriday

Thank you for share great site .

Oh the shame of the wasted years.

After I originally left a comment I seem to have clicked on

the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and

from now on whenever a comment is added I recieve 4 emails with

the same comment. Is there a way you are able to remove me from that service?

Thanks a lot!

Kaizer Chiefs should not forget Ace Ntsoelengoe today 8/5/2006.

I have followed Kaizer Chiefs since 1971 as an 11 year old boy and witnessed all the wizadry of Ace Ntsoelengoe who DIED on this day in 2006. He built the Kaizer Chiefs brand that is a household name today. He did this with Rhyder Mofokeng, Gerald Umgababa Dlamini, Tikkie Khosa, Petrus Ten-Ten Nzimande, Ariel Pro Kgongoane, Pele Blashke form Namibia, Computer Lamola, Malobo Lichaba, Abednigo Skaka Ngcobo, Johnny Magwegwe Mokoena, Nelson Teenage Dladla, Amos Njokweni, Sylvester City Late Kole, Marks Maponyane, Wagga-Wagga, Samora Khulu, Chippa Molatedi, Doctor Khumalo, Ace Khuse, KKK Mthimkhulu, the list goes on. We salute Ace Ntsoelengoe who was voted player of the Century at Chiefs and inducted to the Hall of fame in the US, the only Soccer player to receive such an accolade in Africa. SA and Chiefs in particular should never forget this inimitable black Soccer star.

Many cats prefer horizontal surface to scratch on rather than vertical.

Your pet can use it to sharpen her claws without destroying your furniture.

This is almost feline abuse in the eyes of your precious princess or your precious prince.

my weblog … find a lawyer mn

Very shortly this website will be famous among all blog visitors, due to it’s pleasant posts

Take a look at my site; lose fat (Augustina)

thanks for article..

Secure to roll in the hay that anybody set a

circumstances of fear on football game as I do, avid task

first mate!

Hello, Cool posting. Likely to concern as well as your site within internet explorer, may possibly test this specific? Web browser even so would be the sector boss as well as a large component of other folks leaves from the wonderful writing therefore challenge.

Patson Banda was not born in Malawi. “Sparks” is still well and does occasional work on SABC 1. Always good to hear his views.

The great Ace Ntsoelengoe did not score four goals against Argentina. He created them, Jomo Sono scored them. Even though he did not score all the goals, he possesed the greatest vision ever on Souh African football pitch. His style was comparable to that of Michel Platini.

Gary Bailey never played alongside the “Brixton Tower” Jimmy Joubert at Chiefs. Bailey’s defense had the likes of Mark Tovey and Malawi born Jack Chamangwana.

This post, other than correcting facts, does not wish to take away anything from the story told above.

yo

I read this paragraph completely about the resemblance of most up-to-date and preceding technologies, it’s amazing article.|

The posts is rather significant

Fastidious response in return of this matter with firm arguments and telling all about that.

Hi there every one, here every person is sharing these kinds of experience,

so it’s good to read this website, and I used to visit this website all

the time.

Hello to every body, it’s my first pay a visit of this

web site; this blog includes awesome and truly excellent stuff in support of visitors.

I see you don’t monetize your site, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks

every month because you’ve got high quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra $$$, search

for: Mertiso’s tips best adsense alternative

I have noticed you don’t monetize your site, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn extra bucks every month because you’ve got hi quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra bucks, search for:

Ercannou’s essential adsense alternative