Four years into the Iraq war — “hard to believe,” eh, Mr Wolfowitz? — don’t expect the U.S. media to dwell on the conceptual foundations of this catastrophe. That may be because the media was rather complicit in laying those foundations. But the more interesting question, today, I think, is where the Iraq adventure is going, because its narratives have clearly unraveled, and its strategic purpose — in the sense of attainable goals rather than fantasies — is now far from clear. To be sure, today, Washington is clear only on what it wants to prevent in Iraq, and even then its chances of doing so are slim. Still, as Bush says, that doesn’t mean it can withdraw.

It’s worth noting, in passing, that the decision making structures in the United States are fundamentally dysfunctional to its imperial project — its system of government is democratic (in a plutocratic sort of way), and distributes its flow of information and decision making across a number of bureaucratic command centers that are seldom on quite the same page, and compete for authority and resources — a competition that occurs partly in the public eye, via “leaks” to the media, whose source is invariably the bureaucratic rivals of those who are made to look bad by the story. The executive decision makers are always vulnerable to the limited appetite of the electorate for costly imperial adventures, and the electorate gets to express its impatience every two years by using the ballot box to limit the authority of those directing the current imperial expedition.

The patience of the enemy out in the field, meanwhile, is invariably far deeper than that allowed by U.S. election cycles. Ho Chi Minh knew that; so do the Iraqi insurgents and the Shiites and the Iranians, and the Palestinians and Syrians and everybody else Washington is fighting. The Iraqis are intimately aware of the debate in Washington over withdrawal, and they know that despite the surge of troops, the U.S. will in the near future be forced by domestic pressure to withdraw most of its infantry from Iraqi streets. (No wonder frustrated hawks like Max Boot and Michael O’Hanlon are suggesting that the U.S. military begin outsourcing expeditionary warfare to the satrapies, offering green cards for four years service — just as the British wherever possible sent Indians or Ghurkas to do their fighting.) But even that won’t overcome the bureaucratic internecine warfare. Ask a question as simple as “How could the U.S. occupy Iraq without having a coherent plan?” and the answer is simple: There was a plan, but it was trashed because it had been developed in the State Department, whose personnel hadn’t drunk the Kool Aid of permanent revolution in the Middle East, and therefore couldn’t be trusted. While the neocons might have believed their fantasies about Iraq tranforming itself immediately into a willing and happy satrap of the U.S., the likes of Cheney and Rumsfeld had no inclination to back a long occupation. So, Paul Bremer was sent in without a clue, armed with some old manuals from the occupation of Germany in 1945 (no jokes!) and a civil administration recruited largely from the intern echelon of neocon think-tanks. (Again, no jokes!)

Then there’s the question of the media’s failure to challenge the conceptual frameworks in which the public was prepared for war. I’ll resist the hubristic temptation to reprise the predictive highlights of the 487 pieces of analysis I’ve written for TIME.com over the years on Iraq, but suffice to say that you didn’t need to be a clairvoyant to establish (at the time, not only in retrospect) that the war was based on false premises: Not only the premise that Saddam had some unconventional weapons, but that even if he did, that invading and occupying his country was a wise response. (Think about it, would Iraq be any less of a mess today if the U.S. had actually found a couple of sheds full of mustard gas and even a refrigerator stocked with botulinum toxin?) Nor was it that hard to establish the inevitability that the U.S. occupation of Iraq would stir a nationalist resistance that would be hard to contain — people don’t like being occupied; it makes Arab people feel like the Palestinians, and that inspires them to resist. All this was lost on the coterie of “experts” who have dominated the milquetoast media discussion of Iraq even after they’ve been proved so spectacularly wrong (Kristol, Boot, Krauthammer, Beinart, Hitchens, Packer and so on).

But there’s no value in reprising the morbid jig that sent America lurching into this mess.

The more interesting question, I think, is what is Iraq now? What is the U.S. doing there? What are its objectives, and which of them can be salvaged? And the reason those questions are so interesting is that the original bundle of impulses and objectives that took America into war has now completely unraveled in the brutal reality of Iraq. Not only that, the U.S. long ago lost its ability to shape the outcome, and the agendas of others limit what Washington is able to achieve.

Bush sounded almost comical Monday when he appealed for patience, saying it would take months to secure Baghdad. Perhaps, but pacification of the capital via a massive injection of new troops, four years into the war, is not much of an achievement — and even then, it will happen relatively quickly because the Shiite militias have simply gone to ground to let the U.S. forces sweep their areas unimpeded, and concentrate on the Sunni insurgents.

The Shiite and Sunni political-military formations will be there months from now, and there’s no sign that the current government is able to achieve an accord that would resolve the conflict. Nor is there a credible alternative to the present government — if the best hope is the wannabe-thug Iyad Allawi, suddenly returned from London to try and forge a new coalition, you know Maliki is as good as it gets. And, of course, some of the things Maliki has to do to stay in power are likely to intensify the conflict — not only his alliance with Sadr, but his dependence on the support of the Kurds, who are pressing to complete their takeover of Kirkuk this year, which the Sunni Arabs and Turkey are unlikely to accept. Breaking up the country will cause regional chaos, holding it together offers simply a more contained chaos.

Still, Bush is not wrong in saying that retreating from Iraq will empower forces hostile to the U.S. all over the region. Of course he omits to acknowledge that it already has, but a withdrawal would certainly underscore the image of epic defeat, and would likely plunge the region into chaos as various regional powers moved to secure their stake in the resulting vacuum. So, while there’s not much that can be achieved, cutting bait could result in greater setbacks.

Iraq, then, may no longer simply be a place or a project; instead it has become the morbid condition of contemporary imperial America.

The decision to invade Iraq is not reducible to any single cause or impulse, as both the Administration hacks (including Christopher Hitchens!) and the conspiracy theorists and vulgar-Marxists would have us believe. Just as political power itself rests in a complex web of relations and balances spread over a range of different institutions with different interests and objectives, so must the decision to go to war be explained as the confluence of a range of different impulses into a kind of “perfect storm.”

Even before 9/11 created an easily exploited climate of fear and crude belief among those in power in the necessity of retribution (inspired by the sort of vulgar Orientalism of the Bernard Lewis brigade — funny how those who tell us that “the only language Arabs understand is violence” are those most inclined to converse with the Arab world in that tongue), there were other impulses:

Iraq was not invaded simply because of its vast oil reserves, and yet there’s absolutely no question that winning control over those reserves for Western oil companies was considered a major benefit of going to war — given the broad prescriptions of the Energy Task Force headed up by Cheney two years earlier, it’s simply impossible that the Administration had not factored the oil windfall into its thinking. Saddam was a nuisance in the geopolitical sphere, but once the opportunity presented itself, there was no reason to live with his control over such vast oil reservves.

Iraq was not invaded simply because of the suspicion that it harbored unconventional weapons. Even if it had the weapons unaccounted for by the UN inspectors, those posed no strategic threat to anyone — indeed, it was the very weakness of the Iraqi regime that made it such an appealing beach-head for the launch of a broad strategy to reorder the politics of the region to the advantage of the U.S. and its allies through the application of U.S. military force.

Iraq wasn’t invaded because of a suspicion that it might be in cahoots with al-Qaeda. That was the flimsiest part of the case; indeed, it’s hard to imagine how Colin Powell could keep a straight face making that allegation to the UN Security Council. Al-Qaeda loathed Saddam, and Saddam loathed al-Qaeda. Moreover, neither Saddam nor al-Qaeda represented a significant strategic threat to the U.S. Still, the broad strategy of putting a massive U.S. military presence at the heart of the Arab world was definitely viewed as a means of destroying the emerging challenges to U.S. authority and influence that al-Qaeda was hoping to stir. Partly, this was the crude logic of “retaliation”; partly it was a very specific plan to reorganize the political-military terrain of the region by making Iraq the major staging area of U.S. military operations throughout the region, building 14 permanent bases there from which U.S. power could be projected in all directions (and taking the pressure of hosting the U.S. off the more fragile regime in Saudi Arabia). And the neocons were already talking about bringing down the regimes of Iran, Syria and even Saudi Arabia, all of whom had actually allied with the U.S. to a greater or lesser extent against al-Qaeda.

Iraq wasn’t invaded to spread “democracy” in the Middle East; indeed, democratic elections weren’t even on the agenda as Bremer sought a three-year process to remake the political and economic system under his direct control with no direct elections. It was the pressure from Ayatollah Sistani and the Shiites that forced the U.S. to relent and hold the elections, and once that happened, political control slipped forever out of the hands of the U.S. and the exiles it had cultivated and parachuted in — democracy produced a government closer to Tehran than to Washington. Hobbesian hardmen like Cheney and Rumseld would have had little instinctive enthusiasm for the messianic naivete of the likes of Wolfowitz and the neocons, but their priority may have been to limit the exposure of U.S. troops and its duration, (Rummy) and to hasten the transfer of authority to a kleptocratic Quisling class with whom the likes of Halliburton and the oil companies would love to deal. (Too bad democracy involves letting people vote.)

Plainly, much of that vision lies in tatters. The question is how much of it can be salvaged, and at what cost — or even more gloomily, how can Iraq be managed in ways that limit the extent to which it weakens and imperils U.S. global interests. (It’s no longer plausible to see it as advancing those interests.)

The Baghdad security plan is clearly triage, aggressive defense designed to prevent the capital outside the Green Zone from falling entirely into the hands of insurgents and militias. It’s being tied to political conditions set for the Iraqi government, although it’s already clear that the government is unlikely to meet many of those — the idea of national reconciliation they envisage may not be plausible for the foreseeable future. Interestingly enough, one of the most urgent “benchmarks” set for the Maliki government is the passing of a new oil law. The oil law is characterized in most of the U.S. media simply as a mechanism for fairly sharing oil revenues among the various regions and therefore sects and ethnic groups — but the far more significant portion of the legislation is the fact that it offers up ownership of Iraq’s reserves to foreign oil companies, meaning that, in fact, the revenues available for sharing will be considerably reduced — but the imperial objectivce of acquiring control of Iraq’s oil reserves will be ensured. Although Maliki’s cabinet has accepted the law, it remains to be seen whether the parliament will adopt it. Iraqis are not stupid, and won’t that easily sign away their patrimony no matter how good Christopher Hitchens tells them it will be for them. (Who’d have imagined the Trotskyist contrarian of old not only flakking for the Administration, but also as a shill for Big Oil…)

But whether it’s the troop surge or the oil law, what we’re seeing now are panicky improvisations. And many questions simply remain unanswered — the Administration has studiously dodged ever stating clearly its intentions, or even desires, apropos the permanent bases it has constructed in Iraq. (But Washington is still pouring billions of dollars into constructing them.) But the fact that there’s still no sign of an Iraqi air force or any other military capability to defend the country’s borders tells you that Washington has made no plans to leave Iraq independent, in the sense of capable of defending its sovereignty, any time soon. (Even the Hillary Clinton types talk of pulling U.S. forces out of the cities and deploying them on the borders, as if Iraq is to remain a U.S. protectorate in perpetuity.)

But there simply is no U.S. plan constructed in a modular way that allows maximal aims to be jettisoned in order to ensure the realization of core objectives. It simply unravels, messily.

Much of the U.S. coverage of the troop surge is centered on whether or not it will “work,” with Democrats insisting it won’t and neocons saying it already has. But that depends, very much, on what we mean by “work.” Obviously it won’t defeat the insurgency or the Shiite militias: The commander in charge, General David Petraeus, is a smart counterinsurgency thinker, and he has made clear himself that no action by the U.S. military can secure Iraq — the critical dimension, he insists, remains political: the ability of a new political order to integrate the Sunnis, and to negotiate compacts with the Shiite leadership to whom the militias answer. So, when Petraeus is asked, for example, whether the Mehdi army of Moqtada Sadr could have a legitimate role as a community security force protecting Shiites, he is open to the idea even if Washington’s political echelon isn’t.

It strikes me that Petraeus envisages his mission as a holding operation, to prevent Baghdad from collapsing into anarchy in the hope that freezing the current balance of forces between the sectarian rivals largely in place, the U.S. can create space for a new political compact. While the failed social engineers in Washington may be hoping to remake the political center in Baghdad, their prospects for doing so look increasingly grim. Petraeus is unlikely to be as naive as the political wing of the Administration in imagining that Maliki can be sidelined or Sadr eliminated.

Instead, he’s more likely to encourage discussion with the insurgents, and also the diplomatic process Iraq’s government has initiated with its neighbors, forcing Washington into engaging with Iran and Syria (or creating cover for it to do so). If Iran and Saudi Arabia are able to achieve a compact that stabilizes Lebanon, then such regional horse-trading may yet have something to offer in Iraq. The problem, of course, is that both the domestic political process in Iraq, and the regional diplomacy, are beyond Washington’s control.

What Iraq is, in short, after four years, is an exercise in damage-limitation. The only certainty now is that the U.S. will emerge from the conflict considerably weaker as a global power than when it went in. “Hard to believe,” eh Wolfie, “hard to believe…”

Former Knesset Speaker Avraham Burg was a decorated paratrooper and the son of a prominent conservative cabinet minister before he played a prominent role in Peace Now and the anti-Lebanon war movement. But what got my attention was Burg’s passionate denunciation of the state of contemporary Israel from the perspective of a left-Zionist idealist: “The Israeli nation today rests on a scaffolding of corruption, and on foundations of oppression and injustice… There may yet be a Jewish state here, but it will be a different sort, strange and ugly… The Jewish people did not survive for two millennia in order to pioneer new weaponry, computer security programs or anti-missile missiles. We were supposed to be a light unto the nations. In this we have failed. It turns out that the 2,000-year struggle for Jewish survival comes down to a state of settlements, run by an amoral clique of corrupt lawbreakers who are deaf both to their citizens and to their enemies. A state lacking justice cannot survive.” And so on — read it, it’s a powerful piece. I don’t share Burg’s belief that Zionism itself can be redeemed. But I do share is conviction that Jewish identity is meaningless unless it serves a higher purpose, the purpose of universal justice. And he seems to feel the same way, writing in Haaretz last year that he finds Diaspora Jews who are committed to justice his natural allies rather than fellow Israelis who have turned their backs on it. Exactly. That’s the interesting conversation.

Former Knesset Speaker Avraham Burg was a decorated paratrooper and the son of a prominent conservative cabinet minister before he played a prominent role in Peace Now and the anti-Lebanon war movement. But what got my attention was Burg’s passionate denunciation of the state of contemporary Israel from the perspective of a left-Zionist idealist: “The Israeli nation today rests on a scaffolding of corruption, and on foundations of oppression and injustice… There may yet be a Jewish state here, but it will be a different sort, strange and ugly… The Jewish people did not survive for two millennia in order to pioneer new weaponry, computer security programs or anti-missile missiles. We were supposed to be a light unto the nations. In this we have failed. It turns out that the 2,000-year struggle for Jewish survival comes down to a state of settlements, run by an amoral clique of corrupt lawbreakers who are deaf both to their citizens and to their enemies. A state lacking justice cannot survive.” And so on — read it, it’s a powerful piece. I don’t share Burg’s belief that Zionism itself can be redeemed. But I do share is conviction that Jewish identity is meaningless unless it serves a higher purpose, the purpose of universal justice. And he seems to feel the same way, writing in Haaretz last year that he finds Diaspora Jews who are committed to justice his natural allies rather than fellow Israelis who have turned their backs on it. Exactly. That’s the interesting conversation. On Yom Kippur in 1979, as a young Zionist of the socialist (and atheist) persuasion, I didn’t go to shul; instead I stayed home and read a book I’d found in the shelf of one of my madrichim (older leaders of Habonim): It was Uri Avnery’s “Israel Without Zionism,” and the effect it had was profound. My misgivings about Zionism had been growing, not only because its narrow nationalist concerns seemed at odds with the universal justice that I saw as its purpose, but also because I was better acquainted with its history. In Habonim we knew about events like the Deir Yassin massacre, and didn’t try to hide from them. They were the work, after all, of the Irgun/Likud/Betar, whom we deemed dangerous fascists. But we clung to the idea that our side, the Haganah/Labor side, had remained pure and noble. The Betarim laughed at us; how did we think Israel would have had a Jewish majority were it not for events like Dir Yassin scaring the Palestinians into fleeing? And here came Uri Avnery recounting the same stories, and more, giving the lie to the “miracle” in which 700,000 people simply walked away from their homes in response to Arab radio broadcasts urging them to leave. Avnery chronicled the ethnic cleansing activities of his own unit. And he offered a vision of a union with the Arab world, which later inspired him to be one of the founders of the Israeli peace movement. Definitely more useful than a day spent in shul watching the alte kakkers sniffing snuff to keep themselves awake… Avnery established, for me, the principle that to recognize the truth of Israel’s history, and to renounce Zionism, was not somehow to betray my Jewishness. He was the first Israeli I read saying Israel could not deny the pain it had inflicted on others; facing up to it and acknowledging it was, in fact, the Jewish thing to do.

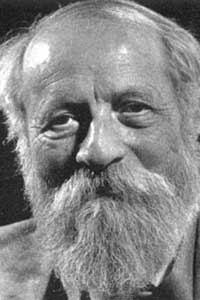

On Yom Kippur in 1979, as a young Zionist of the socialist (and atheist) persuasion, I didn’t go to shul; instead I stayed home and read a book I’d found in the shelf of one of my madrichim (older leaders of Habonim): It was Uri Avnery’s “Israel Without Zionism,” and the effect it had was profound. My misgivings about Zionism had been growing, not only because its narrow nationalist concerns seemed at odds with the universal justice that I saw as its purpose, but also because I was better acquainted with its history. In Habonim we knew about events like the Deir Yassin massacre, and didn’t try to hide from them. They were the work, after all, of the Irgun/Likud/Betar, whom we deemed dangerous fascists. But we clung to the idea that our side, the Haganah/Labor side, had remained pure and noble. The Betarim laughed at us; how did we think Israel would have had a Jewish majority were it not for events like Dir Yassin scaring the Palestinians into fleeing? And here came Uri Avnery recounting the same stories, and more, giving the lie to the “miracle” in which 700,000 people simply walked away from their homes in response to Arab radio broadcasts urging them to leave. Avnery chronicled the ethnic cleansing activities of his own unit. And he offered a vision of a union with the Arab world, which later inspired him to be one of the founders of the Israeli peace movement. Definitely more useful than a day spent in shul watching the alte kakkers sniffing snuff to keep themselves awake… Avnery established, for me, the principle that to recognize the truth of Israel’s history, and to renounce Zionism, was not somehow to betray my Jewishness. He was the first Israeli I read saying Israel could not deny the pain it had inflicted on others; facing up to it and acknowledging it was, in fact, the Jewish thing to do. The early Zionist philosopher who moved to Palestine in 1938 was one of the most prominent advocates, in the years immediately before Israeli statehood, of the idea of a single, binational state for Jews and Arabs founded on the basis of equality. The partition of Palestine, he said, could only be achieved and sustained by violence, which he abhorred. For Buber, the Zionist idea was premised on it fulfilling the Biblical injunction to be a moral “light unto the nations.” But he could already sense that the dominant strain in the Zionist movement was the opposite, and would have the effect, at great moral cost, of simply trying to make the Jews a nation like any other. In this schema of “normalization,” the Jews simply had to acquire a territory and a common language, and the rest would take care of itself. He saw this as a reflection of a longstanding tension inside Judaism: The powerful injunction to make the pursuit of truth and justice the very purpose of Judaism, and he wrote, “the natural desire, all too natural, to be ‘like the nations.’ The ancient Hebrews did not succeed in becoming a normal nation. Today, the Jews are succeeding at it to a terrifying degree.” He advocated Jews and Arabs creating a single democratic state in Palestine in 1948. And he warned that those who pursued sovereignty for a Jewish majority state of Israel were making war inevitable. Referring to the Arab population of Palestine, he asked, “what nation will allow tiself to be demoted from the position of majority to that of a minority without a fight?” He warned that the the path taken in 1948 would extinguish the progressive potential of his idealistic Zionism. Which it did. The moral idealism at the center of the old left-Zionist ideology did not survive contact with the living, real population of Palestine. Buber had the courage and prescience to recognize that and warn the Zionist movement of the moral cul-de-sac down which it was heading.

The early Zionist philosopher who moved to Palestine in 1938 was one of the most prominent advocates, in the years immediately before Israeli statehood, of the idea of a single, binational state for Jews and Arabs founded on the basis of equality. The partition of Palestine, he said, could only be achieved and sustained by violence, which he abhorred. For Buber, the Zionist idea was premised on it fulfilling the Biblical injunction to be a moral “light unto the nations.” But he could already sense that the dominant strain in the Zionist movement was the opposite, and would have the effect, at great moral cost, of simply trying to make the Jews a nation like any other. In this schema of “normalization,” the Jews simply had to acquire a territory and a common language, and the rest would take care of itself. He saw this as a reflection of a longstanding tension inside Judaism: The powerful injunction to make the pursuit of truth and justice the very purpose of Judaism, and he wrote, “the natural desire, all too natural, to be ‘like the nations.’ The ancient Hebrews did not succeed in becoming a normal nation. Today, the Jews are succeeding at it to a terrifying degree.” He advocated Jews and Arabs creating a single democratic state in Palestine in 1948. And he warned that those who pursued sovereignty for a Jewish majority state of Israel were making war inevitable. Referring to the Arab population of Palestine, he asked, “what nation will allow tiself to be demoted from the position of majority to that of a minority without a fight?” He warned that the the path taken in 1948 would extinguish the progressive potential of his idealistic Zionism. Which it did. The moral idealism at the center of the old left-Zionist ideology did not survive contact with the living, real population of Palestine. Buber had the courage and prescience to recognize that and warn the Zionist movement of the moral cul-de-sac down which it was heading.

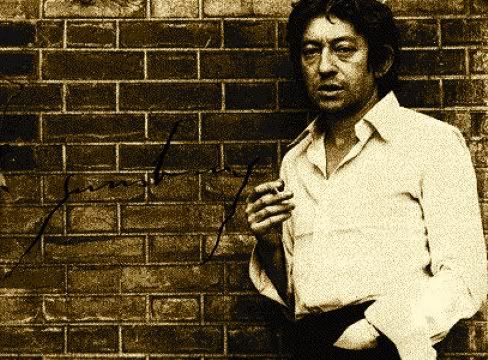

No pop-cultural icon ever rattled France as much as Serge Gainsbourg did, from the moment he burst into notoriety in 1969 with the heavy breathing “Je T’Aime,” the favorite Barmitzvah party slowdance of my era. The French establishment, not exactly the most philo-Semitic bunch, loathed Gainsbourg for his chutzpah, a vaguely ugly Jew who didn’t give a crap about exposing their pretenses and hypocrisies. And why should he? He’d had to wear the yellow star during the Nazi occupation, and he saw just how “courageous” his neighbors had been in standing up to the Nazis (contra the Gaullist myth that all or most of France had been with the Resistance). And if they had a problem with his aesthetic provocations, he wasn’t about to make them feel comfortable. Gainsbourg cut and mixed and mashed, lampooning Frenchness and its denied but nonetheless palpable fascination with America, and committed the ultimate patriotic sin of recording a reggae version of Le Marseillaise (“Aux Armes, Etc.” —

No pop-cultural icon ever rattled France as much as Serge Gainsbourg did, from the moment he burst into notoriety in 1969 with the heavy breathing “Je T’Aime,” the favorite Barmitzvah party slowdance of my era. The French establishment, not exactly the most philo-Semitic bunch, loathed Gainsbourg for his chutzpah, a vaguely ugly Jew who didn’t give a crap about exposing their pretenses and hypocrisies. And why should he? He’d had to wear the yellow star during the Nazi occupation, and he saw just how “courageous” his neighbors had been in standing up to the Nazis (contra the Gaullist myth that all or most of France had been with the Resistance). And if they had a problem with his aesthetic provocations, he wasn’t about to make them feel comfortable. Gainsbourg cut and mixed and mashed, lampooning Frenchness and its denied but nonetheless palpable fascination with America, and committed the ultimate patriotic sin of recording a reggae version of Le Marseillaise (“Aux Armes, Etc.” —

Like a Biblical prophet determined to confront the Biblical Israelites with their moral failings, Amira Hass has dedicated her life to holding up a mirror to the State of Israel so that it can see itself, and its actions, through the eyes of those it has most impacted: the dispossessed and disenfranchised Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza. Her courageous work as an Israeli journalist determined to show her compatriots the effect their policies are having on their immediate neighbors makes her, for me, a living embodiment of Hillell’s insistence that being Jewish means weighing your actions first and foremost on the basis of their effect on others. The daughter of Holocaust survivors who had been communist partisans fighting the Nazis in Europe, Hass has taken up the plight of the Palestinians — she lives in Ramallah, as Haaretz correspondent there — with her parents’ blessing: “My parents came here to Israel naively. They were offered a house in Jerusalem. But they refused it. They said: ‘We cannot take the house of other refugees.’ They meant Palestinians. So you see, it’s not such a big deal that I write what I do – it’s not a big deal that I live among Palestinians.”

Like a Biblical prophet determined to confront the Biblical Israelites with their moral failings, Amira Hass has dedicated her life to holding up a mirror to the State of Israel so that it can see itself, and its actions, through the eyes of those it has most impacted: the dispossessed and disenfranchised Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza. Her courageous work as an Israeli journalist determined to show her compatriots the effect their policies are having on their immediate neighbors makes her, for me, a living embodiment of Hillell’s insistence that being Jewish means weighing your actions first and foremost on the basis of their effect on others. The daughter of Holocaust survivors who had been communist partisans fighting the Nazis in Europe, Hass has taken up the plight of the Palestinians — she lives in Ramallah, as Haaretz correspondent there — with her parents’ blessing: “My parents came here to Israel naively. They were offered a house in Jerusalem. But they refused it. They said: ‘We cannot take the house of other refugees.’ They meant Palestinians. So you see, it’s not such a big deal that I write what I do – it’s not a big deal that I live among Palestinians.”

I think I wept with joy when I first read Primo Levi (The Periodic Table, on a flight from Johannesburg to London in 1989). His was, for me, a matchlessly inspiring example of being Jewish in the world rather than separately from it. A man of science and ethics, fully integrated into Italian society and its most progressive elements, he found himself in Auschwitz not as a result of a Nazi roundup of Italian Jews, but because he was a captured in the course of his work as an anti-Fascist partisan fighter. When the Germans occupied Italy in 1942, he responded as a Jew — not in any narrow, tribal sense (indeed, he didn’t identified as such) but in the expansive, moral sense; in other words, he responded as any decent person with a love of justice and freedom, by joining the partisan underground. Not any separate Jewish organization, but the partisans bound by a common, universal ideology of justice and freedom, in which any Jew should feel comfortable. As did a lot of Italian Jews of his generation: The filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo, most famous for The Battle of Algiers, and also a partisan, was once quoted as saying “I am not an out-and-out revolutionary. I am merely a man of the Left, like a lot of Italian Jews.” Yet, once captured as a leftist partisan, it was the Nazis who reduced Primo Levi’s identity to that of a Jew, in a “racial” sense. His writing — by far the most compelling tales of life and death in Auschwitz — chronicles the Holocaust experience with both scouring emotion and the cool eye of reason, always seeking its universal meanings and implications. His audience, always, is a global community of likeminded rather than one defined on any narrow nationalist basis — Zionism had little use for Primo Levi; his work was only translated into Hebrew after his death.

I think I wept with joy when I first read Primo Levi (The Periodic Table, on a flight from Johannesburg to London in 1989). His was, for me, a matchlessly inspiring example of being Jewish in the world rather than separately from it. A man of science and ethics, fully integrated into Italian society and its most progressive elements, he found himself in Auschwitz not as a result of a Nazi roundup of Italian Jews, but because he was a captured in the course of his work as an anti-Fascist partisan fighter. When the Germans occupied Italy in 1942, he responded as a Jew — not in any narrow, tribal sense (indeed, he didn’t identified as such) but in the expansive, moral sense; in other words, he responded as any decent person with a love of justice and freedom, by joining the partisan underground. Not any separate Jewish organization, but the partisans bound by a common, universal ideology of justice and freedom, in which any Jew should feel comfortable. As did a lot of Italian Jews of his generation: The filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo, most famous for The Battle of Algiers, and also a partisan, was once quoted as saying “I am not an out-and-out revolutionary. I am merely a man of the Left, like a lot of Italian Jews.” Yet, once captured as a leftist partisan, it was the Nazis who reduced Primo Levi’s identity to that of a Jew, in a “racial” sense. His writing — by far the most compelling tales of life and death in Auschwitz — chronicles the Holocaust experience with both scouring emotion and the cool eye of reason, always seeking its universal meanings and implications. His audience, always, is a global community of likeminded rather than one defined on any narrow nationalist basis — Zionism had little use for Primo Levi; his work was only translated into Hebrew after his death.