I.

Avir harim kalul ba’yayin, ve reach oranim…

The opening lines of Naomi Shemer’s legendary Yerushalayim Shel Zahav (Jerusalem of Gold) can still bring goosebumps to my flesh, even decades after I deconstructed and relinquished the mythology connoted by the old Basque lullaby she repurposed as an ode to Israel’s conquest of East Jerusalem in June of 1967. I first heard the song at age 8 in a documentary film shown at my afternoon Hebrew class (ugh!), all gorgeous evening sunshine glowing pink off the old city, as it related the “miracle” of Israel’s “six-day” triumph over its Arab neighbors in that year. And it made me feel good, in an epic kind of way. Already the song had become a kind of anthem, an emotional seduction into the notion of the conquest of East Jerusalem somehow signifying Jewish salvation. Steven Spielberg even planned to include it in the grossly misleading postcard he tacked on to the end of Schindler’s List, in which Holocaust survivors are shown in Jerusalem as if this was somehow a triumph over Nazism, although he dropped the idea after Israeli test audiences found the connection discordant. But rarely has there been a more powerful song in the Israeli imagination, precisely because of the giddily messianic atmosphere that prevailed in Israel in the wake of the war — an atmosphere that blinded Israelis to the calamitous implications of their conquest. But hey, even at age 6, I bought into that atmosphere.

There was no such thing as television in South Africa in 1967, so it was through grainy black-and-white photographs in the evening newspaper that I learned that Mirage jet fighters — the same delta-winged plane flown over my house with great, and occasionally sound barrier-breaking regularity by the South African Air Force to and from nearby Ysterplaat air base, although the ones in the paper bore the Star of David on their wing tips — had destroyed Egypt’s MiG squadrons on the ground. And with those images, and later ones of paratroopers in webbed helmets at the Wailing Wall, that I learned of the “miracle” — Israel, the tiny Jewish state whose map I knew from the blue and white money tin into which we would put a coin every Friday night after Shabbos dinner, had faced down the combined armies of its Arab neighbors, and had dispatched them within six days.  And they had “liberated” our “holiest” site, an old stone wall in East Jerusalem pocked with pubic clumps of weeds, into whose cracks and crannies I was told that Jews could insert notes to be read by God — like a hotel message cubby. (Let’s just say that by the time I got there, at age 17, this bubbemeis about holy stones and a celestial post office only fueled my atheism.) Not only that, they’d made Israel “safe” by “liberating” the whole of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights. In six days! A miracle, like the creation story in Genesis! (Of course, many years later, I would learn that it hadn’t even taken that long; Israel had attacked first and effectively won the war in the opening hours by destroying its enemy’s air forces on the ground — Six Days just sounded like a good name for a war given the creation story.)

And they had “liberated” our “holiest” site, an old stone wall in East Jerusalem pocked with pubic clumps of weeds, into whose cracks and crannies I was told that Jews could insert notes to be read by God — like a hotel message cubby. (Let’s just say that by the time I got there, at age 17, this bubbemeis about holy stones and a celestial post office only fueled my atheism.) Not only that, they’d made Israel “safe” by “liberating” the whole of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights. In six days! A miracle, like the creation story in Genesis! (Of course, many years later, I would learn that it hadn’t even taken that long; Israel had attacked first and effectively won the war in the opening hours by destroying its enemy’s air forces on the ground — Six Days just sounded like a good name for a war given the creation story.)

Even at the age of six, my first year in big school, Israel’s victory had a profound effect on me. The previous year, I had heard my older step-brothers describe a Phys-Ed class being turned into a kind of playful pogrom, in some sort of fighting game that had pitched the Jewish boys against the rest. Being Jewish jocks, they had, according to my brothers’ account over dinner, given as good as they’d gotten, and it was a genuinely playful thing, besides — the sort of playful contest I recall from my older years that often saw a class divide on lines of “Boer against Brit,” i.e. Afrikaans kids against English-speakers, recalling the Boer War. But at six years old, the idea of a small group of Jewish boys being surrounded and set upon by their gentile classmates was absolutely terrifying.

But the news out of Israel in those mid-year months in 1967 was infinitely reassuring. Israel’s dramatic victory had proved that we, the prickly little state or the Jewish boys in their white Phys-ed (we called it PT) vests and shorts, were not to be fucked with. (I remember a similar effect a decade later, after the audacious raid on Entebbe had freed a group of passengers held on a hijacked Air France plane in Uganda — by then, my friends and I were literally accepting congratulations on Israel’s behalf.) And, I know anecdotally as much as anything else, that anyone ever called a “Jewboy” anywhere in the world walked a lot taller after the first week of June in 1967.

But the news out of Israel in those mid-year months in 1967 was infinitely reassuring. Israel’s dramatic victory had proved that we, the prickly little state or the Jewish boys in their white Phys-ed (we called it PT) vests and shorts, were not to be fucked with. (I remember a similar effect a decade later, after the audacious raid on Entebbe had freed a group of passengers held on a hijacked Air France plane in Uganda — by then, my friends and I were literally accepting congratulations on Israel’s behalf.) And, I know anecdotally as much as anything else, that anyone ever called a “Jewboy” anywhere in the world walked a lot taller after the first week of June in 1967.

We were certainly granted the recognition on the playground that the epic victory demanded. The idea of Jews as being weaklings or afraid to fight was buried; white South Africa with its own narrative pitting it as an embattled minority in a sea of hostile neighbors embraced the Israeli victory as an inspiration.  The word “Arab” became synonymous, on the playground and in the classroom, with incompetence and idiocy. “Don’t be an Arab!” I heard a teacher exclaim, more than once in response to a student’s failure to properly carry out his instructions. And, three years after the 1967 war, when the apartheid regime celebrated the tenth anniversary of South Africa’s formal independence from Britain, the ceremony in my school playground saw my Jewish friends and I, in our blue Habonim shirts and scarves and kakhi shorts, line up alongside the boy scouts and the Voortrekkers (the fascist Afrikaner youth movement) to salute the flag and proclaim our loyalty to the Republic (even though the whole point of Habonim was to persuade us to emigrate!). A regime rooted in vicious anti-Semitism and explicit admiration for the Nazis had now come to recognize Israel and its local supporters as a fighting ally in their epic struggle, couched in Cold War language, between white peoples and peoples of color.

The word “Arab” became synonymous, on the playground and in the classroom, with incompetence and idiocy. “Don’t be an Arab!” I heard a teacher exclaim, more than once in response to a student’s failure to properly carry out his instructions. And, three years after the 1967 war, when the apartheid regime celebrated the tenth anniversary of South Africa’s formal independence from Britain, the ceremony in my school playground saw my Jewish friends and I, in our blue Habonim shirts and scarves and kakhi shorts, line up alongside the boy scouts and the Voortrekkers (the fascist Afrikaner youth movement) to salute the flag and proclaim our loyalty to the Republic (even though the whole point of Habonim was to persuade us to emigrate!). A regime rooted in vicious anti-Semitism and explicit admiration for the Nazis had now come to recognize Israel and its local supporters as a fighting ally in their epic struggle, couched in Cold War language, between white peoples and peoples of color.

Die Vaderland (The Fatherland), a newspaper of the apartheid regime, editorialized in 1969, on the occasion of a visit to South Africa by Ben Gurion, “When we, from our side, look realistically at the world situation, we know that Israel’s continued existence in the Middle East is also an essential element in our own security… If our Jewish citizens were to rally to the call of our distinguished visitor — to help build up Israel — their contribution would in essence be a contribution to South Africa’s security.”

South Africa and Israel became intimate allies in the years that followed the ’67 war, with unrepentant former Nazis such as Prime Minister B.J. Vorster welcomed to Israel to seal military deals that resulted in collaboration in the development of weapons ranging from aircraft and assault rifles to, allegedly, nuclear weapons. I remember well how some products of South Africa’s Jewish day-school system, where Hebrew was taught as well as the mandatory Afrikaans, finding themselvse with cushy posting during their compulsory military services — as Hebrew-Afrikaans translators for Israeli personnel working with the SADF. And that alliance raised the comfort level of the South African Jewish community in apartheid South Africa — while a handful of Jewish revolutionaries had made up a dominant share of the white ranks of the national liberation movement, they were largely disowned by the mainstream organized Jewish community, which had chosen the path of quiescence and collaboration with the regime. Their posture, and Israel’s, were now in perfect alignment.

Fruitful collaboration: The Israeli

military called it the Galil, the SADF

called it the R-4, but it was the same gun

Even as I came to recognize and react to the horrors of apartheid, Israel seemed to me to represent a shining alternative. I remember shocking the grownups at a Pesach seder in 1974, my Bar Mitzvah year, by telling them that I would never do my compulsory military service in South Africa. But they smiled and murmured approvingly when I declared that, instead, I would go to Israel and serve in the army there, because that way “I could fight for something I believe in.” (I had, of course, in my cheesy adolescent way, stolen that line from a Jewish character in James A. Michener’s “The Drifters,” who uses it in relation to Vietnam; but the image in my mind when I read it, as when I said it, was of those paratroopers at the Wailing Wall.)

I could not conceive of Israel as in any way complicit in the crimes of apartheid, much less as engaged in its own forms of apartheid. After all, my connection to Israel, by the time I was 14, came largely through Habonim, a socialist-Zionist youth movement whose Zionism was infused with just the sort of left-wing universalism for which my own anti-apartheid subversive instincts yearned. My Habonim madrichim, bearded radicals from the University of Cape Town opened by mind to Marx and Marcuse, Bob Dylan and Yevtushenko, Woodie Guthrie and Erich Fromm. I was already a Jewish atheist, and considered myself a socialist, but in my mind, Israel and Kibbutz were the absolute negation of all that was wrong with South Africa; as a stepping stone to universal brotherhood and equality as expressed in the idealism of early left-wing Zionist thinkers like Ber Borochov, A.D. Gordon and Martin Buber. It became clear to me soon enough (by the time I was 18, to be specific) that their Zionist idealism — and mine — had no connection to the reality of Israel, largely because it ignored the elephant in the room: the Arab population of Palestine.

II.

The war of 1967 was a continuation of the war of 1948, a battle over sovereignty, ownership and possession of the land in what had been British-Mandate Palestine.  Sensing the escalating conflict between the Arab population and the European Jewish settlers who had been allowed by the British, since their conquest of Palestine in 1917, to settle there and establish the infrastructure of statehood — and moved by the impulse to create a sanctuary for the survivors of the Holocaust while avoiding giving most of them the choice of moving to the U.S. or other Western countries — the U.N. recommended in 1947 that Palestine be partitioned, to create separate Jewish and Arab states. The Zionists were disappointed by the plan, because they had hoped to have all of Palestine become a Jewish state. And the fact that it left Jerusalem, where 100,000 Jews lived, within the territory of the Arab zone, albeit run as an international city, was particularly irksome. But the Zionist leadership also knew that the plan was as good as they were going to get via diplomacy, and accepted the plan. (The rest, of course, they would acquire in battle, in 1948 and 1967, in wars that they could blame on their enemies — after all, 40 years after the 1967 war, during which time Israel has been at peace with the enemy it faced on that flank, the West Bank remains very much in Israeli hands, with close to half a million Israelis settled there.)

Sensing the escalating conflict between the Arab population and the European Jewish settlers who had been allowed by the British, since their conquest of Palestine in 1917, to settle there and establish the infrastructure of statehood — and moved by the impulse to create a sanctuary for the survivors of the Holocaust while avoiding giving most of them the choice of moving to the U.S. or other Western countries — the U.N. recommended in 1947 that Palestine be partitioned, to create separate Jewish and Arab states. The Zionists were disappointed by the plan, because they had hoped to have all of Palestine become a Jewish state. And the fact that it left Jerusalem, where 100,000 Jews lived, within the territory of the Arab zone, albeit run as an international city, was particularly irksome. But the Zionist leadership also knew that the plan was as good as they were going to get via diplomacy, and accepted the plan. (The rest, of course, they would acquire in battle, in 1948 and 1967, in wars that they could blame on their enemies — after all, 40 years after the 1967 war, during which time Israel has been at peace with the enemy it faced on that flank, the West Bank remains very much in Israeli hands, with close to half a million Israelis settled there.)

And, of course, war would likely have looked inevitable, because the Arabs were unlikely to accept a deal in which they were, by definition, the losers. Today, Israel insists that the demographic “facts on the ground” must be taken into account in any peace settlement, and demands that it be allowed to maintain the large settlement blocs built on the best land in the West Bank since 1967. And the Bush Administration has formally endorsed this claim. But look at the “facts on the ground” of 1947/8: The Partition Plan awarded 55% of the land to the Jewish state, including more than 80% of land under cultivation. At the time, Jews made up a little over one third of the total population, and owned some 7% of the land. Moreover, given the demographic demands of the Zionist movement for a Jewish majority, the plan was an invitation to tragedy: The population within the boundaries of the Jewish state envisaged in the 1947 partition consisted of around 500,000 Jews and 400,000 Arabs.

Hardly surprising, then, that the Arabs of Palestine and beyond rejected the partition plan.

For the Arab regimes, the creation of a separate Jewish sovereign state in the Holy Land over which the Crusades had been fought was a challenge to their authority; it was perceived by their citizenry as a test of their ability to protect their land and interests from foreign invasion. And so they went to war believing they could reverse what the U.N. had ordered on the battlefield. For the Jews of Palestine in 1948, a number of them having narrowly survived extermination in Europe, the war was a matter of physical survival. Although in the mythology, the war pitted a half million Jews against 20 million Arabs, in truth Israel was by far the stronger and better-organized and better-armed military power. And so what Israel called the War of Independence saw the Jewish state acquire 50% more territory than had been envisaged in the partition plan. The maps below describe the difference between the Israel envisaged by the UN in 1947 and the one that came into being in the war of 1948.

But maps don’t convey the disaster that befell the Palestinian Arabs in 1948. The war also allowed the Zionist movement to resolve its “demographic concerns,” as some 700,000 Palestinian Arabs found themselves driven from their homes and land — many driven out at gunpoint, the majority fleeing in fear of further massacres such as the one carried out by the Irgun at Dir Yassein, and all of them subject to the same ethnic-cleansing founding legislation by passed the new Israeli Knesset that seized the property of any Arab absent from his property on May 8, 1948, and forbad the refugees from returning.

The revised partition effected by the war left hundreds of thousands of Palestinians destitute in refugee camps in neighboring Arab countries, a drama that continues to play out today in northern Lebanon.

And for the next generation of Arab leaders, pan-Arabists and nationalists who overthrew the feeble Western-allied monarchies, the fundamental challenge of their nationalist vision became “redeeming” Arab honor by reversing their defeat of 1948. They tried twice, in 1967 and again in 1973, and failed. But even today, as political Islam supplants nationalism and pan-Arabism as the dominant ideologies of the Arab world, reversing the defeats of 1973, 1967 and 1948 remains a singular obsession.

III.

For Jews of my generation who came of age during the anti-apartheid struggle, there was no shaking the nagging sense that what Israel was doing in the West Bank was exactly what the South African regime was doing in the townships. Even as we waged our own intifada against apartheid in South Africa, we saw daily images of young Palestinians facing heavily armed Israeli police in tanks and armored vehicles with nothing more than stones, gasoline bombs and the occasional light weapon; a whole community united behind its children who had decided to cast off the yoke under which their parents suffered. And when Yitzhak Rabin, more famous as a signatory on the Oslo Agreement, ordered the Israeli military to systematically break the arms of young Palestinians in the hope of suppressing an entirely legitimate revolt, thuggery had become a matter of national policy. It was only when some of those same young men began blowing themselves up in Israeli restaurants and buses that many Israel supporters were once again able to construe the Israelis as the victim in the situation; during the intifada of the 1980s they could not question who was David and who was Goliath. Even for those of us who had grown up in the idealism of the left-Zionist youth movements, Israel had become a grotesque parody of everything we stood for.

For Jews of my generation who came of age during the anti-apartheid struggle, there was no shaking the nagging sense that what Israel was doing in the West Bank was exactly what the South African regime was doing in the townships. Even as we waged our own intifada against apartheid in South Africa, we saw daily images of young Palestinians facing heavily armed Israeli police in tanks and armored vehicles with nothing more than stones, gasoline bombs and the occasional light weapon; a whole community united behind its children who had decided to cast off the yoke under which their parents suffered. And when Yitzhak Rabin, more famous as a signatory on the Oslo Agreement, ordered the Israeli military to systematically break the arms of young Palestinians in the hope of suppressing an entirely legitimate revolt, thuggery had become a matter of national policy. It was only when some of those same young men began blowing themselves up in Israeli restaurants and buses that many Israel supporters were once again able to construe the Israelis as the victim in the situation; during the intifada of the 1980s they could not question who was David and who was Goliath. Even for those of us who had grown up in the idealism of the left-Zionist youth movements, Israel had become a grotesque parody of everything we stood for.

Even those within the Zionist establishment who came through the same tradition were horrified: Former Knesset Speaker Avraham Burg wrote in 2003:

It turns out that the 2,000-year struggle for Jewish survival comes down to a state of settlements, run by an amoral clique of corrupt lawbreakers who are deaf both to their citizens and to their enemies. A state lacking justice cannot survive. More and more Israelis are coming to understand this as they ask their children where they expect to live in 25 years. Children who are honest admit, to their parents’ shock, that they do not know. The countdown to the end of Israeli society has begun.

It is very comfortable to be a Zionist in West Bank settlements such as Beit El and Ofra. The biblical landscape is charming. You can gaze through the geraniums and bougainvilleas and not see the occupation. Travelling on the fast highway that skirts barely a half-mile west of the Palestinian roadblocks, it’s hard to comprehend the humiliating experience of the despised Arab who must creep for hours along the pocked, blockaded roads assigned to him. One road for the occupier, one road for the occupied.

This cannot work. Even if the Arabs lower their heads and swallow their shame and anger for ever, it won’t work. A structure built on human callousness will inevitably collapse in on itself. Note this moment well: Zionism’s superstructure is already collapsing like a cheap Jerusalem wedding hall. Only madmen continue dancing on the top floor while the pillars below are collapsing…

Israel, having ceased to care about the children of the Palestinians, should not be surprised when they come washed in hatred and blow themselves up in the centres of Israeli escapism. They consign themselves to Allah in our places of recreation, because their own lives are torture. They spill their own blood in our restaurants in order to ruin our appetites, because they have children and parents at home who are hungry and humiliated. We could kill a thousand ringleaders a day and nothing will be solved, because the leaders come up from below – from the wells of hatred and anger, from the “infrastructures” of injustice and moral corruption…

Between the Jordan and the Mediterranean there is no longer a clear Jewish majority. And so, fellow citizens, it is not possible to keep the whole thing without paying a price. We cannot keep a Palestinian majority under an Israeli boot and at the same time think ourselves the only democracy in the Middle East. There cannot be democracy without equal rights for all who live here, Arab as well as Jew. We cannot keep the territories and preserve a Jewish majority in the world’s only Jewish state – not by means that are humane and moral and Jewish.

Many pro-Israel commentators today lament what they see as a shift in the Palestinian political mindset from the secular nationalism of Fatah to a more implacable Islamist worldview, supposedly infinitely less reasonable because it couches its opposition to Israel in religious terms. Yet, what is often overlooked is how the Israeli victory in 1967 effected a similar shift

in Zionist ideology away from the secular nationalism of Ben Gurion’s generation to a far more dangerous religious nationalism. Tom Segev, my favorite Israeli historian, writes that the 1967 war resulted in many Israelis coming to see the army as an instrument of messianic theology. The knitted yarmulke of the settlers moving to colonize the West Bank in the wake of the 1967 victory came to replace the cloth cap of the socialist kibbutznik as the symbol of Zionist pioneering. Segev quotes from Rav Kook, the founder of the settlement movement: “There is one principal thing: the state. It is entirely holy, and there is no flaw in it… the state is holy in any and every case.”

The settlement of Maale Adumim, on the West Bank.

Its permanence signifies that whatever their intentions,

the Zionists created a single (apartheid) state for Jews

and Palestinians after 1967

The religious Zionists saw the West Bank and holy land to be “redeemed,” or “liberated” by settlement, and with the tacit support of all Israeli governments since then (and the more active support of some) they rushed to build permanent structures and settle a civilian population there, in defiance of international law, in order to preclude the possibility of returning that land to the Palestians as a basis for peace.

As David Remnick notes in a review of some of the literature on 1967, many Israelis quickly realized that the “Six Day War” had brought about a potential disaster for the Zionist project, because Israel now found itself not only in control of all of the territory of British-Mandate Palestine, but also all of its current inhabitants. He quotes Amos Oz’s dark warning

“For a month, for a year, or for a whole generation we will have to sit as occupiers in places that touch our hearts with their history. And we must remember: as occupiers, because there is no alternative. And as a pressure tactic to hasten peace. Not as saviors or liberators. Only in the twilight of myths can one speak of the liberation of a land struggling under a foreign yoke. Land is not enslaved and there is no such thing as a liberation of lands. There are enslaved people, and the word “liberation” applies only to human beings. We have not liberated Hebron and Ramallah and El-Arish, nor have we redeemed their inhabitants. We have conquered them and we are going to rule over them only until our peace is secured. “

But the religious-nationalists and Likudniks, who had always imagined a “Greater Israel” [EM] the Betar kids I knew in Cape Town used to wear a silver pendant on their chests, depicting a state of Israel running from the Nile to the Euphrates, and they used to sing a song called “Shte Gadot La Yarden” (“Both Sides of the Jordan” [EM] had something else in mind. As I’ve noted previously, it was my South African Habonim elders on Kibbutz Yizreel, in 1978, who first warned my generation that the settlement policies of the new Likud government would turn Israel into an apartheid state — Israel, they said, could not afford to give the Palestinians on the West Bank the vote, but the objective of the settlements was to ensure that Israel did not withdraw from the land it had conquered. The result would be that Israel would rule over its Palestinian residents without giving them the rights of citizens — the very essence of the apartheid regime back home.

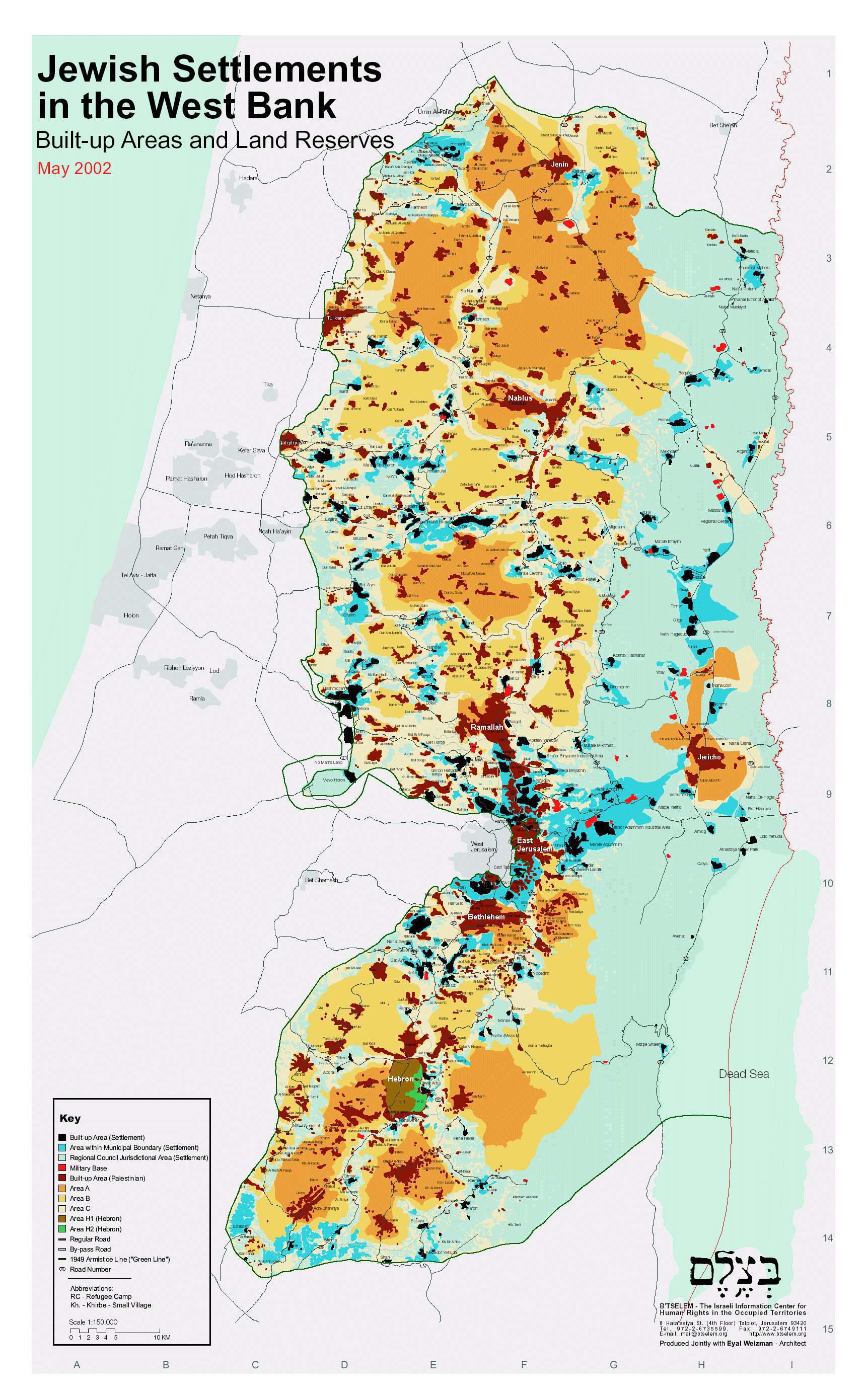

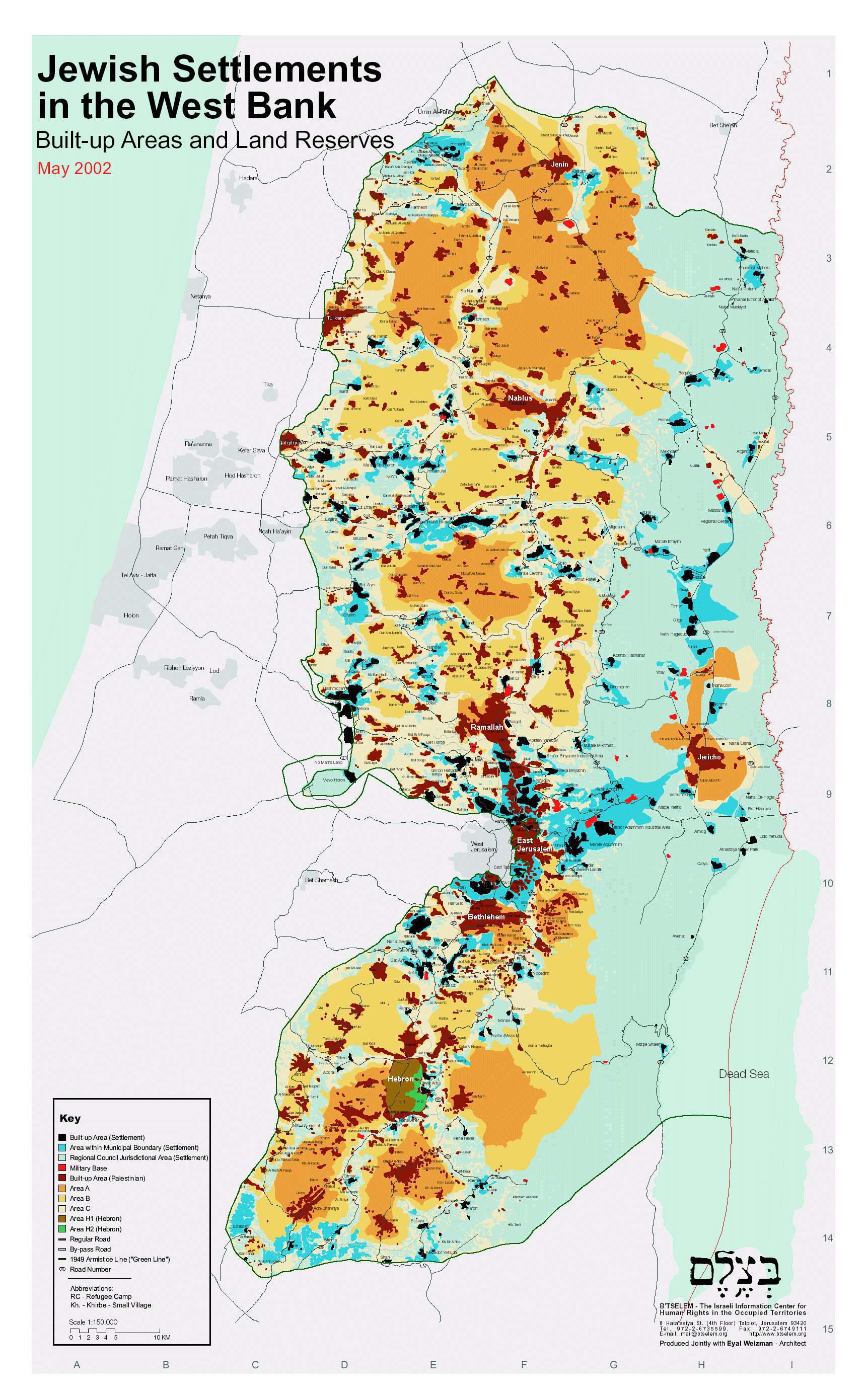

And that is, indeed, what had transpired. Today, the West Bank is carved up by hundreds of Israeli settlements, and roads and land reserved for settlers. And they have no intention of leaving, while no Israeli government for the foreseeable future will muster the political strength to be able to remove them (even if that was their intent).

The black and blue areas are Israeli settlements, and the white parts are the roads and land under Israeli control

For an enlarged version of this map, click here.

Today, talk of a two-state solution to the conflict must reckon with the facts on the ground. The 1947 Partition plan left the Palestinians with 45 percent of the territory of Palestine; the 1948 war left them holding onto 22 percent, which fell into Israeli hands in 1967. Even when it talks about a two-state solution, Israel still demands to keep some of the best lands and the key water sources within that 22 percent. A simple glance at the map above should be enough to raise serious questions about the viability of a separate, sovereign Palestinian nation-state. It’s hard to imagine such an entity, blessed with few natural resources and with hardly any independent economic base, maintaining an independent economic existence, even as it is forced to accomodate hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees returning from refugee camps in Lebanon and elsewhere (as most versions of the two-state plan envisage). Indeed, such an entity may well have the feel of an enlarged refugee camp, whose survival is largely dependent on handouts.

When it conquered the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, Israel put the Palestinian population of those territories under the rule of the Israeli state. For forty years, now, the entire population of British-Mandate Palestine has been governed by a single state. The difference, of course, is that those who live within Israel’s 1967 borders have democratic rights, while those outside are governed by an Israeli colonial and military administration. The extent of Palestinian “authority” in those territories — even Gaza — remains entirely circumscribed by Israeli power.

Suddenly panicked by the demographic implications of the apartheid order its 1967 conquests have created, Israeli leaders talk of “separating” from the Palestinians, as if they can dispense with the problem by drawing political boundaries and building a wall around self-governing Palestinian enclaves (Ariel Sharon himself used the analogy with South Africa’s apartheid Bantustan policy to describe the idea.) But the Gaza experience has made clear the limits of that option.

For the Palestinian population, and their Arab neighbors, the crisis of 1948 has never been resolved. And the Israelis, for the last 40 years, by colonizing the West Bank and East Jerusalem, have squandered whatever opportunities their victory of 1967 presented for changing the dynamic — instead, they have sought to cling to elements of the “Greater Israel” they created in that year, and in the vain hope that the Palestinians will some day surrender in exchange for whatever Israel chooses to offer them.

But precisely because they have continued to expand Israel since 1967, they have dimmed the prospects for a new partition creating a viable Palestinian state separate from Israel. Today, more than ever, the fate of the Israelis is inextricably, and intimately linked to the fate of the Palestinians — and vice versa. The lasting legacy of the 1967 war is the bi-national state it created in the old territory of British-Mandate Palestine.

It with great pleasure that I introduce guest columnist Sean Jacobs, a fellow Capetonian who these days divides his time between Brooklyn and Ann Arbor, where he is an assistant professor of Communication Studies and African Studies at the University of Michigan. He describes himself as “a frustrated journalist” (is there any other kind?), and in his spare time edits the online edition of Chimurenga magazine. In 2004 he directed the Ten Years of Freedom Film Festival in New York City in April 2004.

It with great pleasure that I introduce guest columnist Sean Jacobs, a fellow Capetonian who these days divides his time between Brooklyn and Ann Arbor, where he is an assistant professor of Communication Studies and African Studies at the University of Michigan. He describes himself as “a frustrated journalist” (is there any other kind?), and in his spare time edits the online edition of Chimurenga magazine. In 2004 he directed the Ten Years of Freedom Film Festival in New York City in April 2004. meager cinematic background — the film Le noir de … (Black Girl) about a young Senegalese immigrant domestic working for a French family in the Antibes. The film, the first feature directed by a black African, was hailed at the time by New York Times critic A.H. Weiler (in now outdated language) as “put[ing] a sharp, bright focus on an emerging, once dark African area and on a forceful talent with fine potentials.” Sembene died this week at 84 after an illustrious career, saluted by another New York Times critic, A.O. Scott, for being as uncompromising in his criticism of Africa’s post-liberation regimes as he had been of French colonial domination. More importantly, Scott pointed out, Sembene was also passionate about celebrating the equality of Africa with the West: “He believed that Africans would experience true liberation when they threw off European models and discovered their own, homegrown versions of modernity.”

meager cinematic background — the film Le noir de … (Black Girl) about a young Senegalese immigrant domestic working for a French family in the Antibes. The film, the first feature directed by a black African, was hailed at the time by New York Times critic A.H. Weiler (in now outdated language) as “put[ing] a sharp, bright focus on an emerging, once dark African area and on a forceful talent with fine potentials.” Sembene died this week at 84 after an illustrious career, saluted by another New York Times critic, A.O. Scott, for being as uncompromising in his criticism of Africa’s post-liberation regimes as he had been of French colonial domination. More importantly, Scott pointed out, Sembene was also passionate about celebrating the equality of Africa with the West: “He believed that Africans would experience true liberation when they threw off European models and discovered their own, homegrown versions of modernity.” The result of all that planning and effort (the real editor Graydon Carter lists Liebovitz’s flight schedule in his “editor’s letter”) is hardly extraordinary — though I was intrigued by, if not sure what to make of, the curious shot of Madonna apparently sniffing Maya Angelou.

The result of all that planning and effort (the real editor Graydon Carter lists Liebovitz’s flight schedule in his “editor’s letter”) is hardly extraordinary — though I was intrigued by, if not sure what to make of, the curious shot of Madonna apparently sniffing Maya Angelou.

As an Australian anti-Zionist Jew writing about Israel/Palestine, the rules of the game are made clear to me on an almost daily basis. All Jews must support the “Jewish State,” no matter what. Any action carried out by the state is defensible, justified and moral. Any public criticism of Israel will be assumed to be anti-Semitic; if Israel is to be criticized at all, it should only be in hushed tones and in private. Dare to challenge these rules, and you can expect to be bombarded with hate-mail, death-threats and public abuse, invariably from fellow Jews.

As an Australian anti-Zionist Jew writing about Israel/Palestine, the rules of the game are made clear to me on an almost daily basis. All Jews must support the “Jewish State,” no matter what. Any action carried out by the state is defensible, justified and moral. Any public criticism of Israel will be assumed to be anti-Semitic; if Israel is to be criticized at all, it should only be in hushed tones and in private. Dare to challenge these rules, and you can expect to be bombarded with hate-mail, death-threats and public abuse, invariably from fellow Jews. This meant separating Zionism from Judaism, and recognizing that being a Jew didn’t mean automatic identification with every Israeli action. This Jewish identity had to not be solely defined through what was “good for the Jews”, but on the universal principles of justice as espoused by the Jewish prophets, i.e. by creating a state that treats all citizens as equal. No religiously based state – Muslim, Christian or Jewish – is able to achieve this, and Israel is no exception. Instead, many Jews continue to identify with Israel despite its flagrant violations international norms, denying those or blaming them on the victims. Just last week, on the 40th anniversary of the Six Day War,

This meant separating Zionism from Judaism, and recognizing that being a Jew didn’t mean automatic identification with every Israeli action. This Jewish identity had to not be solely defined through what was “good for the Jews”, but on the universal principles of justice as espoused by the Jewish prophets, i.e. by creating a state that treats all citizens as equal. No religiously based state – Muslim, Christian or Jewish – is able to achieve this, and Israel is no exception. Instead, many Jews continue to identify with Israel despite its flagrant violations international norms, denying those or blaming them on the victims. Just last week, on the 40th anniversary of the Six Day War,

And they had “liberated” our “holiest” site, an old stone wall in East Jerusalem pocked with pubic clumps of weeds, into whose cracks and crannies I was told that Jews could insert notes to be read by God — like a hotel message cubby. (Let’s just say that by the time I got there, at age 17, this bubbemeis about holy stones and a celestial post office only fueled my atheism.) Not only that, they’d made Israel “safe” by “liberating” the whole of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights. In six days! A miracle, like the creation story in Genesis! (Of course, many years later, I would learn that it hadn’t even taken that long; Israel had attacked first and effectively won the war in the opening hours by destroying its enemy’s air forces on the ground — Six Days just sounded like a good name for a war given the creation story.)

And they had “liberated” our “holiest” site, an old stone wall in East Jerusalem pocked with pubic clumps of weeds, into whose cracks and crannies I was told that Jews could insert notes to be read by God — like a hotel message cubby. (Let’s just say that by the time I got there, at age 17, this bubbemeis about holy stones and a celestial post office only fueled my atheism.) Not only that, they’d made Israel “safe” by “liberating” the whole of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights. In six days! A miracle, like the creation story in Genesis! (Of course, many years later, I would learn that it hadn’t even taken that long; Israel had attacked first and effectively won the war in the opening hours by destroying its enemy’s air forces on the ground — Six Days just sounded like a good name for a war given the creation story.) But the news out of Israel in those mid-year months in 1967 was infinitely reassuring. Israel’s dramatic victory had proved that we, the prickly little state or the Jewish boys in their white Phys-ed (we called it PT) vests and shorts, were not to be fucked with. (I remember a similar effect a decade later, after the audacious raid on Entebbe had freed a group of passengers held on a hijacked Air France plane in Uganda — by then, my friends and I were literally accepting congratulations on Israel’s behalf.) And, I know anecdotally as much as anything else, that anyone ever called a “Jewboy” anywhere in the world walked a lot taller after the first week of June in 1967.

But the news out of Israel in those mid-year months in 1967 was infinitely reassuring. Israel’s dramatic victory had proved that we, the prickly little state or the Jewish boys in their white Phys-ed (we called it PT) vests and shorts, were not to be fucked with. (I remember a similar effect a decade later, after the audacious raid on Entebbe had freed a group of passengers held on a hijacked Air France plane in Uganda — by then, my friends and I were literally accepting congratulations on Israel’s behalf.) And, I know anecdotally as much as anything else, that anyone ever called a “Jewboy” anywhere in the world walked a lot taller after the first week of June in 1967. The word “Arab” became synonymous, on the playground and in the classroom, with incompetence and idiocy. “Don’t be an Arab!” I heard a teacher exclaim, more than once in response to a student’s failure to properly carry out his instructions. And, three years after the 1967 war, when the apartheid regime celebrated the tenth anniversary of South Africa’s formal independence from Britain, the ceremony in my school playground saw my Jewish friends and I, in our blue Habonim shirts and scarves and kakhi shorts, line up alongside the boy scouts and the Voortrekkers (the fascist Afrikaner youth movement) to salute the flag and proclaim our loyalty to the Republic (even though the whole point of Habonim was to persuade us to emigrate!). A regime rooted in vicious anti-Semitism and explicit admiration for the Nazis had now come to recognize Israel and its local supporters as a fighting ally in their epic struggle, couched in Cold War language, between white peoples and peoples of color.

The word “Arab” became synonymous, on the playground and in the classroom, with incompetence and idiocy. “Don’t be an Arab!” I heard a teacher exclaim, more than once in response to a student’s failure to properly carry out his instructions. And, three years after the 1967 war, when the apartheid regime celebrated the tenth anniversary of South Africa’s formal independence from Britain, the ceremony in my school playground saw my Jewish friends and I, in our blue Habonim shirts and scarves and kakhi shorts, line up alongside the boy scouts and the Voortrekkers (the fascist Afrikaner youth movement) to salute the flag and proclaim our loyalty to the Republic (even though the whole point of Habonim was to persuade us to emigrate!). A regime rooted in vicious anti-Semitism and explicit admiration for the Nazis had now come to recognize Israel and its local supporters as a fighting ally in their epic struggle, couched in Cold War language, between white peoples and peoples of color.

Sensing the escalating conflict between the Arab population and the European Jewish settlers who had been allowed by the British, since their conquest of Palestine in 1917, to settle there and establish the infrastructure of statehood — and moved by the impulse to create a sanctuary for the survivors of the Holocaust while avoiding giving most of them the choice of moving to the U.S. or other Western countries — the U.N. recommended in 1947 that Palestine be partitioned, to create separate Jewish and Arab states. The Zionists were disappointed by the plan, because they had hoped to have all of Palestine become a Jewish state. And the fact that it left Jerusalem, where 100,000 Jews lived, within the territory of the Arab zone, albeit run as an international city, was particularly irksome. But the Zionist leadership also knew that the plan was as good as they were going to get via diplomacy, and accepted the plan. (The rest, of course, they would acquire in battle, in 1948 and 1967, in wars that they could blame on their enemies — after all, 40 years after the 1967 war, during which time Israel has been at peace with the enemy it faced on that flank, the West Bank remains very much in Israeli hands, with close to half a million Israelis settled there.)

Sensing the escalating conflict between the Arab population and the European Jewish settlers who had been allowed by the British, since their conquest of Palestine in 1917, to settle there and establish the infrastructure of statehood — and moved by the impulse to create a sanctuary for the survivors of the Holocaust while avoiding giving most of them the choice of moving to the U.S. or other Western countries — the U.N. recommended in 1947 that Palestine be partitioned, to create separate Jewish and Arab states. The Zionists were disappointed by the plan, because they had hoped to have all of Palestine become a Jewish state. And the fact that it left Jerusalem, where 100,000 Jews lived, within the territory of the Arab zone, albeit run as an international city, was particularly irksome. But the Zionist leadership also knew that the plan was as good as they were going to get via diplomacy, and accepted the plan. (The rest, of course, they would acquire in battle, in 1948 and 1967, in wars that they could blame on their enemies — after all, 40 years after the 1967 war, during which time Israel has been at peace with the enemy it faced on that flank, the West Bank remains very much in Israeli hands, with close to half a million Israelis settled there.)

For Jews of my generation who came of age during the anti-apartheid struggle, there was no shaking the nagging sense that what Israel was doing in the West Bank was exactly what the South African regime was doing in the townships. Even as we waged our own intifada against apartheid in South Africa, we saw daily images of young Palestinians facing heavily armed Israeli police in tanks and armored vehicles with nothing more than stones, gasoline bombs and the occasional light weapon; a whole community united behind its children who had decided to cast off the yoke under which their parents suffered. And when Yitzhak Rabin, more famous as a signatory on the Oslo Agreement, ordered the Israeli military to systematically break the arms of young Palestinians in the hope of suppressing an entirely legitimate revolt, thuggery had become a matter of national policy. It was only when some of those same young men began blowing themselves up in Israeli restaurants and buses that many Israel supporters were once again able to construe the Israelis as the victim in the situation; during the intifada of the 1980s they could not question who was David and who was Goliath. Even for those of us who had grown up in the idealism of the left-Zionist youth movements, Israel had become a grotesque parody of everything we stood for.

For Jews of my generation who came of age during the anti-apartheid struggle, there was no shaking the nagging sense that what Israel was doing in the West Bank was exactly what the South African regime was doing in the townships. Even as we waged our own intifada against apartheid in South Africa, we saw daily images of young Palestinians facing heavily armed Israeli police in tanks and armored vehicles with nothing more than stones, gasoline bombs and the occasional light weapon; a whole community united behind its children who had decided to cast off the yoke under which their parents suffered. And when Yitzhak Rabin, more famous as a signatory on the Oslo Agreement, ordered the Israeli military to systematically break the arms of young Palestinians in the hope of suppressing an entirely legitimate revolt, thuggery had become a matter of national policy. It was only when some of those same young men began blowing themselves up in Israeli restaurants and buses that many Israel supporters were once again able to construe the Israelis as the victim in the situation; during the intifada of the 1980s they could not question who was David and who was Goliath. Even for those of us who had grown up in the idealism of the left-Zionist youth movements, Israel had become a grotesque parody of everything we stood for.

Political hegemony is achieved when a narrow group of people is able to convince a wider society that the group’s own, narrow interests, in fact, represent the general interest or the “greater good.” Nowhere is there currently a more visible (if artless) example of such a pursuit of hegemony than in Washington’s efforts to get Iraq’s politicians to pass the oil law drafted under U.S. tutelage. That oil law is packaged as the key to national reconciliation in Iraq, forcing the Iraqis to more equitably share oil revenues. What that packaging leaves out, of course, is that the bulk of those oil revenues, under the law’s provisions, would be controlled by foreign oil companies.

Political hegemony is achieved when a narrow group of people is able to convince a wider society that the group’s own, narrow interests, in fact, represent the general interest or the “greater good.” Nowhere is there currently a more visible (if artless) example of such a pursuit of hegemony than in Washington’s efforts to get Iraq’s politicians to pass the oil law drafted under U.S. tutelage. That oil law is packaged as the key to national reconciliation in Iraq, forcing the Iraqis to more equitably share oil revenues. What that packaging leaves out, of course, is that the bulk of those oil revenues, under the law’s provisions, would be controlled by foreign oil companies.  Much of the U.S. media greeted the election of Nicolas Sarkozy as if the French had elected a White House ally to pull themselves out of their morbid decline. Guest contributor Bernard Chazelle explains why the White House will be disappointed by Sarkozy, and offers fascinating insights into everything from economics to anti-semitism to explain why the U.S. media doesn’t understand France in the first place.

Much of the U.S. media greeted the election of Nicolas Sarkozy as if the French had elected a White House ally to pull themselves out of their morbid decline. Guest contributor Bernard Chazelle explains why the White House will be disappointed by Sarkozy, and offers fascinating insights into everything from economics to anti-semitism to explain why the U.S. media doesn’t understand France in the first place.  There’s something a little misleading in the media reports that routinely describe the fighting in Gaza as pitting Hamas against Fatah forces or security personnel “loyal to President Mahmoud Abbas.” That characterization suggests somehow that this catastrophic civil war that has killed more than 25 Palestinians since Sunday is a showdown between Abbas and the Hamas leadership — which simply isn’t true, although such a showdown would certainly conform to the desires of those running the White House Middle East policy. The Fatah-dominated security forces in Gaza answer to the warlord Mohammed Dahlan, long ago anointed by the White House to play the kind of role of a Palestinian Pinochet, and given the backing to beef up his forces to take down Hamas.

There’s something a little misleading in the media reports that routinely describe the fighting in Gaza as pitting Hamas against Fatah forces or security personnel “loyal to President Mahmoud Abbas.” That characterization suggests somehow that this catastrophic civil war that has killed more than 25 Palestinians since Sunday is a showdown between Abbas and the Hamas leadership — which simply isn’t true, although such a showdown would certainly conform to the desires of those running the White House Middle East policy. The Fatah-dominated security forces in Gaza answer to the warlord Mohammed Dahlan, long ago anointed by the White House to play the kind of role of a Palestinian Pinochet, and given the backing to beef up his forces to take down Hamas.  So how could a British Prime Minister move so seamlessly from being Bill Clinton’s best friend on the global stage to being being ideologically and militarily joined at the hip with President George W. Bush? Guest contributor Gavin Evans believes the answer lies in a personality flaw that has been known to overcome liberals and lefties when they get too close to those who hold the real power.

So how could a British Prime Minister move so seamlessly from being Bill Clinton’s best friend on the global stage to being being ideologically and militarily joined at the hip with President George W. Bush? Guest contributor Gavin Evans believes the answer lies in a personality flaw that has been known to overcome liberals and lefties when they get too close to those who hold the real power.