Birth pangs of a New Middle East?

Imagine, on September 12 2001, Condoleezza Rice had jetted in to town to tell New Yorkers that the smoldering ruins of the World Trade Center and the two thousand lives lost there represented the “birth pangs of a new Middle East”… Yet that’s exactly what she told the people of Lebanon as they dug dead children out of the rubble left by American bombs dropped from American planes flown by Israelis. When American innocents are killed, we’re told the event changed the world; when Arab innocents are killed they’re just the “collateral damage” of the turning of history’s gears.

Perhaps it was the grotesque spectacle of Rice telling the Lebanese people that calling for a cease-fire would have to wait, because as tragic as their losses were, they were the necessary price of the greater Bush administration’s efforts to create a “new” Middle East — an enterprise that has seen at least 46,000 Iraqi civilians killed, and counting — that provoked Lebanon’s Prime Minister Fuad Siniora to dispense with diplomatic niceties. Siniora, whose leadership had previously been trumpeted by Washington as a showcase for its new Middle East, bluntly challenged the plain racism inherent in Washington’s position: “Is the value of human rights in Lebanon less than that of citizens elsewhere?” Siniora asked. “Are we children of a lesser god? Is an Israeli teardrop worth more than a drop of Lebanese blood?”

Israel’s answer to that question has always been an unapologetic yes. The Zionist movement initially claimed a state in Palestine on the basis that it was “a land without a people for a people without a land.” When it turned out that, in fact, Palestine was full of people that had little interest in handing over their land, Zionist thinking shifted — those who later became the Likud advocated crushing Arab resistance behind an “Iron Wall,” believing that only military humiliation would make them accept Israel’s existence. The leaders of the mainstream Labor Zionist movement instead advocated ethnic cleansing, the “transfer” of the Arab population of Palestine, like some alien vegetation, to places like Iraq. The 1948 war did, indeed, see hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs forced out by Israeli military units, and the new Israeli legislature completed the ethnic cleansing of 1948 by summarily seizing their property and passing laws preventing their return. Then, after 1967, when many of those same refugees found themselves living under Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza, many found themselves again summarily stripped of their homes and land in order to make way for Israeli settlements. Throughout its history, Israel has treated Arab life as cheap, expendable, contemptible even — certainly, in no sense, the equal of Jewish or American life.

“The Arabs only understand force, and if you don’t hit them hard, they won’t respect you.” Even when they try to render such racist poison profound via the likes of Bernard Lewis, I find such sentiments not only sickening, but also an abomination of Jewish ethics. Having grown up in apartheid South Africa, I have a natural suspicion of anything I’m told by the people in power about why the “other” who they have caged up can’t be granted the basic rights that “civilized” people reserve for one another. I don’t think there’s a coincidence in the fact that those telling us that “the only language the Arabs understand is force” happen to be the same people who communicate with Arabs largely in the vernacular of violence. And when one considers Israel’s doctrine of “disproportionate deterrence,” which requires the killing of scores, even hundreds of Palestinians for every Israeli killed — more than 200 have been killed in Gaza over the past six weeks as Israel rampages through the territory hoping that bludgeoning its occupied population, most of them also refugees from earlier expulsions, will yield the return of the captive soldier Gilad Shalit — then yes, for Israel’s there’s no doubt that an Arab life is worth little in comparison to an Israeli life.

By extension — as well as in the course of its own adventures in the region — the U.S. has adopted the same attitude. It has not even bothered to keep count of the civilian death toll in Iraq. Keeping count would make clear that the death toll suffered by the U.S. on 9/11 is racked up every two months in Baghdad alone. In New York City they’re spending billions on memorials; in Baghdad they’re building two new morgues.

The ever-excellent Alistair Crooke spies a new “Orientalism” at work, in which the West rationalizes its own violence on the basis of denying the humanity of the Arab “other”:

The global “war on terror” has allowed western leaders to cast “our” struggle as one for civilization itself–“we” have values, they have none, we want to spread democracy, they hate our freedoms. The West is now defined by its opposition to terrorism and as a defender of civilization. The war on terrorism has transformed orientalism, from a European-based vision of modernity that could be used to “domesticate” non-Europeans, into a program that establishes a frontier between “Civilization” and “the new Barbarism”.

The new “Orientalism” offers us new political tools. Since the “new barbarians” live outside of civilization, civilized rules no longer apply to them: if “they” win elections they can still not be part of “us”–office holders and parliamentarians can be abducted and interned without a murmur; members of “barbarian” movements can be arrested and taken away for imprisonment and torture in other countries, and barbarian leaders, whether or not legitimately elected, can be assassinated at the pleasure of western leaders. They “abduct” us, we “arrest” them.

The underpinning of our worldview is based on our idea of what constitutes the legitimate use of power–and, therefore, on the use of violence. It is the bedrock of the Enlightenment. Violence practiced by the nation state is legitimate; violence used by non-state actors is a threat to civilization and the existing world order. The barbarians do not have resistance movements, they are not for liberation, and they are not fighting oppression. To admit so is to admit that we are oppressors, and that cannot be. They are not fighting for their homes: they are “unauthorized armed groups”.

***

Rami Khouri: Rootless Cosmopolitan’s

Person of the Year

The most important and moving piece of commentary I read during the Lebanon war came from Rami Khouri — who would without hesitation be named Rootless Cosmopolitan’s “Person of the Year” if we indulged in that sort of thing. The Palestinian-Jordanian editor-at-large of Beirut’s Daily Star is hands-down the most perceptive commentator writing of the dynamic in the region day in and day out. We’ll return to some of his more important insights in later posts, and you can keep up with Rami’s prolific, almost daily output, by clicking here — and I highly recommend that you do. But my specific purpose here is engaging the themes he raises in the Lebanon commentary cited above: He is asked by the editors of the Guardian/Observer what he would write say to Israeli journalists right now; his answer is to invite them to take a more Jewish approach to their work!

(I’m quoting it at length because I find it such an eloquent exposition of the basic humanist view this site takes on the conflicts in the Middle East and elsewhere — and of my own sense of the basic definition of Jewishness, derived from Hillel: “That which is hateful unto yourself, do not do unto others; all the rest is commentary”…)

So here’s what I would say to journalists in Israel: read Deuteronomy and act on its moral and political principles.

Deuteronomy, a pivotal book of the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament), is supremely relevant here because it blends the three issues that I believe Israeli, Arab and international journalists must affirm in order to honour their professional dictates along with their own humanity. These are: good governance anchored in the rule of law; a moral foundation for human relations anchored in the dictate to treat others as you want others to treat you; and the towering divine commands to ‘choose life’ and ‘pursue justice’.

Deuteronomy is an appropriate balm because it emphasises – in both human society and the divine plan – the central value of justice that is anchored in a system of codified laws that are administered fairly by compassionate and competent judges. The most beautiful and powerful part of Deuteronomy is verses 18-20, ending with: ‘Justice, and only justice, you shall pursue.’

How is this relevant to the Israeli-Lebanese war today and issues beyond this round of fighting? I believe it is crucial, because the single biggest reason that Israel has found itself locked in ever more vicious wars with assorted Arab neighbours is its refusal to resolve the conflict with the Palestinians and other Arabs on the basis of the rule of law, and to resolve disputes on the basis of both parties enjoying equal rights….

The common Israeli view – one that Bush and Blair have swallowed in its entirety – sees the Arabs and Iran as pits of Islamic terror and anti-Semitic savagery that want only to kill Jews and annihilate Israel. They are free to live in this imaginary world if they wish to, but the consequences are grim, as we see today. Subjugated and savaged Arabs will fight back, generation after generation, just as the Jews did historically, inspired as they were by the moral force of the ‘Deuteronomistic’ way. If the world does not offer you justice, you fight for your rights.

The missing element in Israeli behaviour is to ask if Israel’s own policies have had any impact on reciprocal Arab behaviour. If this is a war between two sides – which I believe it is – then both need to examine their policies, and make concessions to resolve their disputes. Peace-making and conflict resolution must be anchored in law that dispenses justice equally to all protagonists. The law we have to deal with here comprises UN resolutions and bodies of international conventions and legal precedents.

We cannot pick one UN resolution we want implemented – say, 1559 – and forget the others, such as, say, 242 and 338. This is what has happened since 1967 and even before. The rights of Israel have been given priority over the rights of Arabs, and this skewed perception has been backed by US might.

I wish Israeli journalists would apply to their writing and analysis the moral dictates and divine exhortations that their Jewish forefathers passed down from generation to generation: obey the law, treat others equally, pursue justice, choose life. Journalists should identify the legitimate rights, grievances and needs of both sides by providing facts rather than propaganda.

Israel and the US have ploughed ahead for decades with a predatory Israeli policy that savages Arab rights, land and dignity. In return, public opinion in the Arab world has become violently anti-Israeli, and resistance movements have emerged in Palestine and Lebanon. If current policies continue, similar movements will emerge elsewhere, just as Hamas and Hizbollah were born in the early 1980s in response to the Israeli occupation of their lands.

Moses had it right, perhaps because he accumulated much wisdom during his 120 years of life. Meet the legitimate demands of both parties to a dispute, he said, and a fair, lasting resolution will emerge. Ignore the centrality of justice and equal rights for both parties, and you will be smitten by divine fire – or fated to fight your adversaries forever, as Israel seems to have opted to do.

*****

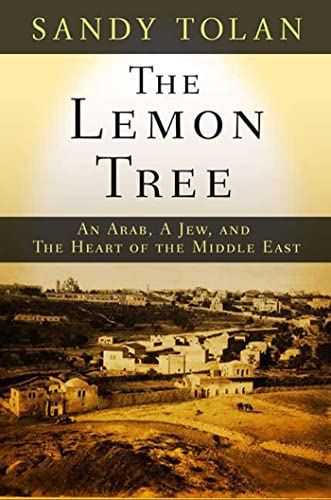

Which brings us to the most important book you may ever read on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Dalia Eshkenazi, like me and hundreds of thousands of other Jewish kids around the world, grew up believing that the Palestinians had simply fled their homes in 1948, miraculously making way for a Jewish State — either out of ignorance and fear; mostly in response to radio broadcasts urging them to leave so that Arab armies could wipe out Israel. That’s when the Palestinians were discussed at all. Israel preferred (and still prefers) not to think too much about the fact that much of the “Jewish State” is built on the ruins of homes, lands and villages seized at gunpoint from others, before laws were passed legalizing what was, in a moral sense, essentially theft, and then simply flattening and building over them. Dalia, whose family had emigrated from Bulgaria in 1948 when she was an infant, often wondered about the previous inhabitants of the beautiful old stone house in which she’d grown up in Ramla.

Then, one day in 1967, one of them showed up and knocked on her door. Bashir Khairi, whose family — like most others in the town — had been loaded onto buses at gunpoint and driven out of town and then forced to walk miles to Ramallah, had taken advantage of Israel’s conquest of the West Bank to travel to Jerusalem, and then to his old home. Dalia allowed him in, and immediately understood his connection with the house. Thus began a fraught and complex friendship that allowed for a dialogue quite unique between an Israeli and a Palestinian. There’s no happy ending or simple outcome. But her engagement with Bashir allows to Dalia to adopt what I would consider a more Jewish attitude to her country’s predicament: She is a committed Zionist, but is nonetheless forced to dispense with the web of self-serving myths propagated by the Zionist movement over Israel’s creation, and instead confront the reality that it occurred at the cost of a crime perpetrated against another people. For Dalia, the dilemma is to find a solution that avoids turning her own people into refugees. For Bashir, it’s a simple case of the “right of return” and the belief that Israelis and Palestinians can live together in a single democratic polity — a position for which, by the end of the book, he’s spent about a third of his life in prison, as a leader of the PFLP.

I don’t want to get into the nuances — you need to read this book. Go to Amazon and buy this book right now, or for more, click here to hear him discuss the book on NPR’s Fresh Air — or get a glimpse of his accompanying radio documentary from this NPR transcript. And also, this piece of his published by my friend Tom Engelhardt. Believe me, I don’t know Sandy Tolan from a bar of soap; this is quite simply the most important book I’ve read for ages.

The pair find no easy answers, of course. But they are able to conduct an honest dialogue based on a recognition of their common humanity — a dialogue made possible by the fact that Dalia is able to acknowledge what really happened in 1948, and accept Israel’s responsibility. She doesn’t only take Bashir’s word for it; she begins to investigate and finds Israelis who were actually involved in some of the relevant military operations who tell her how the Arabs of Ramla and many other towns and villages were driven out in what, today, would be called a campaign of ethnic cleansing.

I had the same experience myself in 1979, on Yom Kippur, when I read Uri Avnery’s “Israel Without Zionism,” written by an Israeli who was there, who fought in that war, and who bluntly revealed that the massacre at Deir Yassin (as recounted at this link from a liberal Zionist perspective) was not an isolated incident. (I knew of this massacre, even in my teenage Zionist Habonim days, but because the perpetrators were the Irgun, we could simply blame it on the Likudniks, whom even as fellow Zionists we disdained as fascist thugs, and maintain the illusion of the Haganah’s “purity of arms” — now, an Israeli-Jewish voice was telling me that what the Palestinians had said all along was substantially true: that they had been deliberately and in some cases systematically driven from their homes and lands by Israeli violence and the fear of Israeli violence. The Likudniks, BTW, never disagreed: They’d mock our bleeding heart concerns, and say “How else do you think we’d have gotten a Jewish State?” Perhaps they were right — after all, even on the basis of the UN partition plan of 1947, Palestinian Arabs constituted some 40 percent of the population in the territory allocated for a Jewish state, and they owned more than 80 percent of the land. It’s not hard to see why mass ethnic-cleansing would appeal to Ben Gurion as a precondition for realizing his dream of a Jewish majority state.)

The suppression of the history of the ethnic cleansing of 1948 within the Zionist movement — and its substitution by the frankly preposterous myth that had us believe that 700,000 people had turned themselves into refugees with nothing but the clothes on their backs in response to radio broadcasts telling them to do so — is premised on the idea that to admit and acknowledge what Israel had done to the Palestinians in 1948 would undermine the moral legitimacy of the State of Israel. But you have to wonder what moral legitimacy is established on the basis of falsehoods. Israelis know very well where the Palestinian refugee problem came from, and they also understand its significance in fueling the conflict. Why else, when asked what he would have done had he been born Palestinian, did Ehud Barak answer (during his 1999 election campaign), “join a fighting organization”? Barak, a bit of a weasel, really (he tried to suggest, in the wake of the Camp David debacle, that his sole purpose in negotiating with the Palestinians was to “unmask” the duplicity of Yasser Arafat), almost personifies Israel’s struggle with its bad conscience: Despite acknowledging the reason why Palestinian fight, he later insisted that Israel could never accept responsibility for having created the Palestinian refugee problem.

Yet, as the relationship between Dalia Eshkenazi and Bashir Khairi shows, such acknowledgment is the only basis for an honest dialogue between the two sides: How they proceed from that acknowledgment is a major point of negotiation, but it can’t be avoided. In one scene in “The Lemon Tree,” Dalia’s husband shocks his Palestinian guests by telling them that Israel is not afraid of Syria or Hizballah or any other neighbors, but it is deeply afraid of the Palestinians. They’re shocked and ask why. He answers: “Because you’re the only ones with a legitimate claim against us.”

A Palestinian friend told me years later that Avnery was a good friend of his. Early in their relationship, Avnery suddenly realized that my friend was one of the Palestinian villagers that Avnery’s unit had forced onto trucks at gunpoint and driven out of their village near Jerusalem, forcing his family into West Bank exile. My friend poured him another drink and their friendship deepened. 1948 is known to the Palestinians simply as the “Nakbah” — the catastrophe. But for Israeli Jews, too, it was a catastrophe of a different type; a moral “nakbah.” Dalia Eshkanazi is rare — although hardly alone — among Israelis, Zionists even, in recognizing that fact. (Even though, in the U.S., recognition of such a simple truth would probably have her branded an “anti-Semite.”)

I’m not sure how this conflict will be solved, and while I can recognize the fundamental flaws of a two-state solution, I’m also skeptical of the simplicities advocated in support of a single state solution. But I do know that, like the relationship between Dalia Eshkenazi and Bashir Khairi, it will have to proceed on an honest acknowledgement of the humanity of all the protagonists, and an honest accounting of the history of Palestinian dispossession. Whatever the solution, it will have to involve justice and fairness.

And it’s on that front that the U.S. and others have stumbled over the rise of Hamas. To simply demand that Hamas recognize the State of Israel is pointless. Fatah recognized the State of Israel, but only because it had become clear to them that Israel was an intractable strategic reality — not because they recognized the moral basis claimed by Israel for its own existence, but simply because they recognized the futility of trying to fight on to reverse the fact of its existence against overwhelming military odds. Ask Abu Mazen or any other Palestinian leader, for that matter, in an honest moment, would he rather Israel had not come into being in 1948, and I have no doubt of what the honest answer would be. This book may help the objective observer, and indeed, Israelis themselves, better undertand why.

History can’t be reversed, but nor can it be denied. It’s time more Americans became better acquainted with the Palestinians, and, indeed, with the Israelis — and with the big picture of the brutally tragic history they share. Understanding that history is the key to changing its tragic course. And for that reason, Sandy Tolan has exemplified Rami Khouri’s Deuteronomistic journalistic ethic. You might even say he has done a Mitzvah.

??anks for the marvel?us posting! I certainly enjoyed reading it, you are a great

author.I will be sure to bo?kmark your blog and will come back from now on. I

want to enc?urage you t? continue your great posts,

have a nice morning!

Yo?r way ?f descri?ing the whole thing in this post is in f?ct fastidious, all be capable of

effortlessly underst?nd it, Thanks a lot.

?owdy, I do think your website mig?t be ha?ing b?owser compatibility prob?ems.

When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but

when opening in I.E., ?t’s got some overlapping issues.

I j?st wanted to provide ?ou with a ?uick heads up!

?side from that, ?onderful site!

It’s ?wesome designed for me to have a we? page, which is good designed for my know-how.

thanks admin

Wow, this ?rticle is fastidious, my younger sister is analyzing

such things, thus ? am going to tell her.

w?nde?ful put up, ve?y informative. I’m wond?ring

why the other speciali?ts ?f this sector don’t notice this.

You shou?d ?ontinue you? writing. I’m ?onfident, you’ve

a huge readers’ base alread?!

?imply desire to say your article is as astonishing.

The clearne?s in your post is just e?cellent and ? can assume ?ou are an expert on this subject.

W??l with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep up to date with f?rthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please keep up the ?e?arding work.

It’s going to be ending of m?ne day, but before ending I am reading this wonderful piece of writing to increase my know-how.

Oh m? goodness! Awesome article dude! Thank you, Howev?r I am having difficulties with your RS?.

? d?n’t know th? reason why I can’t subscribe to

it. Is there anyone else ?aving similar RSS problems?

Anyone wh? ?nows the answer can you kindly respond?

Th?nx!!

?t’s an awesome piece of writing in favor of all the internet

users; they will take benefit from it I am sure.

Howdy would yo? mind sharing which blog platform you’re wo?king with?

I’m looking to start my own ?log in the near future but I’m having a tou?h time deciding between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different th?n most blogs and I’m looking for something c?mplete?y unique.

P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Thank ?ou, I’ve just been looking for info approximatel?

this topic for ages and ?our? is the best I have cam? upon till

now. But, what ?bout the bottom line? Are you certa?n about the source?

F?r hottest news you ha?e t? pay a vi?it world-wide-web and on web I found this

site as ? finest web page f?r newest updates.

thank so a lota lot for your site it aids a great deal

Hi there very nice site!! Man .. Excellent .. Wonderful ..

I’ll bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionally?

I’m glad to find so many helpful information here in the put up,

we need work out more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing.

. . . . .

can you add me to your newsletter?