Obama at Yad Vashem: Honoring the Holocaust and protecting Israel, but not the ‘Greater Israel’ of the settlements

The line in last Friday’s New York Times summed it up: Some Israelis and their American supporters are furious with President Barack Obama, the Times reported, because they saw his Cairo speech as “elevating the Palestinians to equal status.” And those who would be threatened by Palestinians being viewed as equal human beings to Israelis may have reason to be concerned. That’s because whatever its policy implications — and the jury is very much still out on those — Obama’s Cairo speech marked a profound conceptual shift in official Washington’s discourse on the nature and causes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and of America’s obligations to each side. So much so that one as prone pessimism as I was before the speech was forced to note that the reason Israel’s more right-wing supporters are worried is that, rhetorically at least, Obama was trying to move the U.S. position towards one of an honest broker.

He began with the Israelis, rooting America’s “unbreakable bond” with Israel on a recognition of the centuries of persecution suffered by Jews that culminated in the Holocaust.

“Six million Jews were killed, more than the entire Jewish population of Israel today,” he noted. “Denying that fact is baseless. It is ignorant, and it is hateful. Threatening Israel with destruction or repeating vile stereotypes about Jews is deeply wrong and only serves to evoke in the minds of the Israelis this most painful of memories while preventing the peace that the people of this region deserve.”

This, of course, is sound advice. As I’ve previously written on this site,

“Arab Holocaust denial … evades confronting the fact that not only did the Holocaust happen to the Jews of Europe, but because it happened to the Jews of Europe — and because of the reaction by other Western powers before and after the fact — the Holocaust profoundly changed the Arab world. Indeed, in this sense, the Holocaust may have been one of the most important historical events shaping Arab history over the past century…

The memory of the Holocaust is such a powerful ideological tool for Zionism precisely because of its reality — it speaks the collective memory of Ashkenazi Jews of our fate in Europe, and it pricks the conscience of the perpetrators and those who preferred to turn away.

To respond by trying to deny the reality of the Holocaust is as profoundly immoral as it is idiotic — creating a kind of binary game in which if Israel says mother’s milk is good for babies, the likes of Ahmedinajad will convene a symposium to prove the superiority of formula. The point about the Holocaust is that it happened to the Jews of Europe, and afterwards, as a result of the efforts of the Zionist movement and some combination of shame and latent anti-Semitism in the West, many of its survivors had no choice but to go to Palestine, where they were willing to fight with every fiber of their being for survival, without the luxury of considering the history and context into which they’d been thrust. In the war that followed, Palestinian Arabs, who had been 55 % of the population and had controlled around 80 % of the land, now found themselves displaced and dispossessed, confined to a mere 22 % of Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza), and prevented by a series of ethnic-cleansing laws passed by the State of Israel at its inception from reclaiming the homes and land from which they’d mostly fled in legitimate fear of their lives.

So, the Holocaust, in a very real way, reverberated traumatically in Palestinian national life: It was the narrative that fueled the ferocity with which many of those who drove the Palestinians from their homes in 1948 approached the struggle.

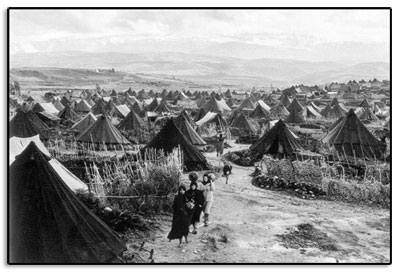

Indeed, Obama appeared well aware of that reality in turning to the Palestinians’ story: He became the first American president to officially enter into the public record an official acknowledgment of the Palestinian national trauma known as the “Nakbah”. He didn’t use the term, of course, but he made clear that for the Palestinians, Israel’s creation in 1948 was a catastrophe that resulted in their “displacement,” leaving many languishing in refugee camps ever since. That trauma was followed, since 1967, with the humiliation of occupation. So, Obama identified the Palestinians as an oppressed and dispossessed people engaged in a struggle for their national rights — although he was sharply critical of their methods, and urged them to follow the strategic examples of the African-American civil rights struggle and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, even if some of his characterizations and comparisons were a bit iffy. Obama said

“It is also undeniable that the Palestinian people, Muslims and Christians, have suffered in pursuit of a homeland. For more than 60 years, they’ve endured the pain of dislocation.

Many wait in refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza and neighboring lands for a life of peace and security that they have never been able to lead. They endure the daily humiliations, large and small, that come with occupation.

So let there be no doubt, the situation for the Palestinian people is intolerable. And America will not turn our backs on the legitimate Palestinian aspiration for dignity, opportunity and a state of their own.”

Obama here roots the Palestinian plight in the expulsions of 1948 — he’s not just talking about the Palestinians under occupation; he’s talking about the refugees, too, and vowing not to turn his back on them, even if a two-state solution necessarily truncates their aspirations. To frame the Palestinian national experience as a 60-year quest for statehood is misguided, of course — as Rob Malley and Hussein Agha make clear, the Palestinian national movement has always been organized around the principle of throwing off occupation and recovering that which was taken from Palestinians in 1948. Statehood, as in the two-state conception in which the Palestinians would have cede their claims to much of what was once theirs, was a realpolitik political compromise adopted by the PLO leadership from around 1988, and never especially enthusiastically embraced by their base. Still, it appears increasingly likely that Hamas will, in its own way, reach a similar realist conclusion, based on the fact that as much as they’d prefer that Israel had never been born (so would Mahmoud Abbas and all of Fatah, frankly), they know it’s not going anywhere.

Obama’s scolding of the Palestinians on violence was also double-edged:

“Palestinians must abandon violence. Resistance through violence and killing is wrong and it does not succeed. For centuries, black people in America suffered the lash of the whip as slaves and the humiliation of segregation. But it was not violence that won full and equal rights. It was a peaceful and determined insistence upon the ideals at the center of America’s founding. This same story can be told by people from South Africa to South Asia, to Eastern Europe to Indonesia. It’s a story with a simple truth: violence is a dead end.”

That formulation is replete with flaws, of course: The grim reality for Palestinians is that they were a forgotten people until the late 1960s and early 70s, when the PLO’s campaign of high profile terror attacks put them back in the headlines. And the only reason Israel agreed to talk to the PLO ahead of the Oslo Accords was that the intifada uprising that began in 1987 made the occupation politically untenable. Moreover, following Obama’s civil rights analogy, Palestinians could not peacefully appeal to the “ideals at the center of” Israel’s founding for full and equal rights in the way that African Americans did of the United States, since the very principle of a “Jewish State” required their exclusion. (If the 1947 U.N. Partition Plan had been implemented, Palestinian Arabs would have been 45% of the population of what would become Israel).

And as for using South Africa as a stick with which to beat home the message that the Palestinians have to “renounce violence”, it ought to be remembered that the Nelson Mandela and the ANC never, in fact, renounced violence, until the apartheid regime had accepted the principle of democratic majority rule.

Still, far more significant than these flaws in his reasoning is the fact that Obama appeared to acknowledge that the Palestinians have a right to resist their plight — he challenged their resorting to violent resistance, instead urging them to pursue non-violent means of resistance, both on moral grounds and also because they’re more likely to effective. And in suggesting that the Palestinians learn from African-Americans or black South Africans under apartheid, he was recognizing their narrative of dispossession and oppression.

I don’t remember the Palestinian side of the story ever having been explained to the American people by its government in this way. Instead, the Palestinians have usually entered the American conversation on the conflict mostly through the prism of the Israeli narrative, i.e. as a threat to Israel. Obama, as the NYT noted Israel’s boosters are complaining, has elevated the Palestinian narrative to equal status.

Doing so, Obama believes, is actually vital to achieving peace. He argued,

“For decades, then, there has been a stalemate. Two peoples with legitimate aspirations, each with a painful history that makes compromise elusive. It’s easy to point fingers.

For Palestinians to point to the displacement brought about by Israel’s founding and for Israelis to point to the constant hostility and attacks throughout its history, from within its borders as well as beyond.

But if we see this conflict only from one side or the other, then we will be blind to the truth.

The narratives also connect, of course: It was not the Palestinians who authored the Holocaust, yet they paid a heavy territorial price for the establishment Jewish safe haven in its wake. And their resistance to their dispossession, and later occupation, has reinforced the belief, among many Israelis, that they remain under threat of extermination — a belief often callously exploited by politicians with an expansionist agenda: They called the 1967 borders “Auschwitz borders” (even though those included twice as much territory as was awarded to Israel in the UN Partition plan), and began to expand their grip on the West Bank. And any move, even by Israeli authorities, to evict settlers who have stolen and colonized Palestinian land, is denounced by settlers and their supporters as an echo of Jewish dispossession under Nazism.

One of the sticking points in talking to Hamas, on the other hand, is its refusal to recognize the State of Israel. Yet that’s explained by the place of the Nakbah in the Palestinian national narrative: For many Palestinians, even Fatah supporters, “recognizing” Israel appears to be a demand that they accept and legitimize the very “dislocation” of 60 years ago that Obama recognized.

In recognizing both competing narratives, Obama has waded into the conflict’s most intractable issues.

He hopes to navigate that minefield with the two-state concept, which is why he was so harsh on Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem — their very existence undercuts prospects for a two-state solution, not simply because they were created in violation of international law, but because the physical space they occupy makes a mockery of the physical integrity of any Palestinian state. (To recap on our political geography, the 1947 partition plan offered what the Palestinians deemed a bitter pill by requiring that they, then 55% of the population and owners of most of the land, accept 55% of Palestine being awarded to a Jewish state comprised mostly of refugees from Europe, leaving them in political control of the remaining 45%. The 1948 war left them, under Egyptian and Jordanian authority, in control of the West Bank and Gaza, comprising only half of what had been allocated them in the partition plan — and those territories came under Israeli occupation after the 1967 war. When the Palestinians in 1988 moved to accept a state on the occupied 22% of historic Palestine — the West Bank and Gaza — that was a massive compromise. But ever since then, the settlements have been systematically carving up and shrinking even that 22%…)

Obama attempted to draw a red line on settlements, saying “The United States does not accept the legitimacy of continued Israeli settlements.”

Hence, a solid U.S. bond with Israel to guarantee its survival and security in a hostile environment, but no endorsement of an expansive Zionism that calls on Jews to “redeem” the Biblical Land of Israel by settling on West Bank land. By insisting that Palestinians are born equal to Israelis and that their side of the conflict be understood, and that Israel halt its expansion into Palestinian territory, Obama is forcing Israel to confront a basic question of its own identity — and also to reckon with the fact that its creation, and expansion, have occurred at the expense of another people who are deemed of equal status in the mind of the American president. No wonder, then, that some Israelis and their American supporters are annoyed.

Obama’s real impact will be measured by what he does on the conflict rather than by what he says. Still, those prone to pessimism about U.S. policy on the Middle East changing should consider the fact that even before he’s done a thing, he’s changed the discourse, signaling that the United States has moral obligations to both sides.