Shortly before I left my native Cape Town, South Africa, for New York in 1993, much of the city’s middle class was seized by a frenzy of greed organized into something called “The Aeroplane Game.” It was a simple pyramid scheme in which “passengers” were recruited, as $200 a pop, and when the bottom row of “seats” was filled, the “pilot” at the top of the pyramid took the $1600 of the newcomers, and everyone moved up a notch — as long as new “passengers” kept joining, everyone was assured of winning. But any fool not blinded by greed could see that sooner or later, there’d be hundreds or thousands of “passengers” left stranded on the tarmac. The game only worked as long as people could be persuaded to have confidence in the idea that the game could keep growing and growing, and that everyone would get rich. Mercifully, local law enforcement put a stop to it before too many people were burned.

Shortly before I left my native Cape Town, South Africa, for New York in 1993, much of the city’s middle class was seized by a frenzy of greed organized into something called “The Aeroplane Game.” It was a simple pyramid scheme in which “passengers” were recruited, as $200 a pop, and when the bottom row of “seats” was filled, the “pilot” at the top of the pyramid took the $1600 of the newcomers, and everyone moved up a notch — as long as new “passengers” kept joining, everyone was assured of winning. But any fool not blinded by greed could see that sooner or later, there’d be hundreds or thousands of “passengers” left stranded on the tarmac. The game only worked as long as people could be persuaded to have confidence in the idea that the game could keep growing and growing, and that everyone would get rich. Mercifully, local law enforcement put a stop to it before too many people were burned.

A lot of the Marxism my generation was taught on university campuses in the early ’80s was fundamentally misguided, but it did instill in me a healthy skepticism of any notion that wealth can simply be conjured out of thin air, or that “confidence” is the basis of an economy — an economy can’t keep expanding simply because people believe that it will keep expanding. That’s not Marxism, I suppose; that’s just common sense — the sort of common sense that says if a society keeps consuming more than it produces, it will get into very big trouble. Or that a society that not only bases its consumption on debt levels that its real economic output can’t sustain, but actually turns debt into a commodity to fuel a speculative market, is courting a very hard landing. (The sort of common sense that, when you expressed it during the dot-com bubble, was like being, to borrow a line from Abby Hoffman, a spoilsport at an orgy.)

The mantra that the collapse of the serial-bubble economy centered on Wall Street for the past two decades is simply a crisis of confidence is as widespread as it is flawed. It is confidence — groundless pollyannaish optimism in greed-driven denial of the iron laws of economic gravity — that got us into this mess. Confidence is what got those poor Capetonians buying “aeroplane game” tickets even though the law of geometric progression dictated that the vast majority would lose their money; and confidence, driven by falsehoods peddled by the barons of the “ownership society”, is what got tens of millions of Americans spending money they never had based on an assumption that the value of their homes and of their investments on the stock exchange would keep on expanding exponentially.

Restoring confidence in the credit system may prevent a cataclysmic meltdown in the U.S. economy, but it won’t fix the long-term decline based on fundamental ailments that the bubble-driven stock market and real estate booms of the past decade have simply deferred. Instead of manically watching the Dow yo-yo from day to day, we should simply recognize that it has been vastly overvalued for some time. Until such time as America’s economy (the real economy, not the fetish market of financial services) has been restored to some semblance of health — a generational project, unfortunately, given the devastation wrought by a generation of Reaganomics and, it must be said, by its “New Democrat” imitators — any dramatic recovery in the Dow will be brittle, based on false confidence or some new “bubble.”

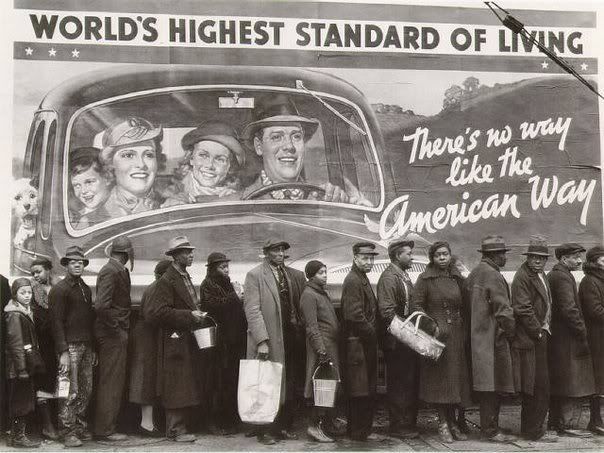

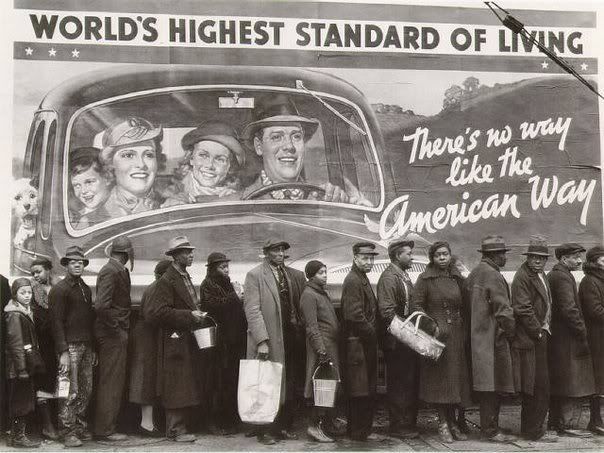

When you’re looking for someone to diagnose a very dark situation, who better to turn to than Mike Davis. In a must-read commentary on the ever-excellent TomDispatch (which now features podcasts!), Davis laments the absence of any discussion on the presidential campaign trail of the deeper crisis, which is not simply in the stock market and credit system, but in the real economy that has long been eclipsed by a financial services industry that trades in debt and other “exotic financial instruments”, and a stock market that for far too long has had precious little connection to the well-being of the real economy. Davis attacks what he calls McCain’s “preferential option for the rich,” but also raises concern over Obama’s vagueness, and the fact that he has “made only passing reference to the next phase of the crisis: the slump of the real economy and likely mass unemployment on a scale not seen for 70 years.”

Davis writes,

With baffling courtesy to the Bush administration, [Obama] failed to highlight any of the other weak links in the economic system: the dangerous overhang of credit-default swap obligations left over from the fall of Lehman Brothers; the trillion-dollar black hole of consumer credit-card debt that may threaten the solvency of JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America; the implacable decline of General Motors and the American auto industry; the crumbling foundations of municipal and state finance; the massacre of tech equity and venture capital in Silicon Valley; and, most unexpectedly, sudden fissures in the financial solidity of even General Electric.

The current bailout is going to subject generations of Americans to expanded public debt and domestic austerity — the U.S. is going to spend trillions of dollars it doesn’t have simply repairing the mess made on Wall Street; and that doesn’t even begin to address the crisis in the real economy. Where are the jobs going to come from to replace the millions that have been lost over the past two decades, and which will now hemorrage at a perilous rate? How will America fund the massive overhaul urgently required in its basic infrastructure? How will it educate a new generation of Americans to compete in a global economy when the option of debt-leveraged college tuition moves rapidly beyond the reach of much of the middle class?

It was telling that John McCain’s first response to the current crisis was to offer the old chestnut that “the fundamentals of the economy are sound.” On the contrary, the fundamentals of the economy are the deeper problem than simply a freezing up of credit markets. As Davis writes, “We are seeing the consequences of a perverse restructuring that began with the presidency of Ronald Reagan and which has inverted the national income shares of manufacturing (21% in 1980; 12% in 2005) and those of financial services (15% in 1980; 21% in 2005).”

Many Democrats are far too smug in blaming this simply on the excesses of Reagan and now Bush. They authored it, of course, but it would be wrong to let Bill Clinton off the hook. As I wrote recently,

The measure of the success of the Reagan revolution, and its trans-Atlantic soulmate, Thatcherism, was that they managed to turn their own ideological agendas on economic and financial policy into conventional wisdom. So complete was the hegemony of their ideas on shrinking government, free markets, deregulation and privatisation that they were embraced by their opposition parties: Bill Clinton sought to distinguish himself from his party’s New Deal consensus by calling himself a “New Democrat” – and sought to emphasise continuity with some of Reagan’s basic principles of fiscal policy.

Over in Britain, Tony Blair rechristened his party “New” Labour to distinguish it from its social-democratic roots. So successful was his embrace of Thatcher’s free-market revolution that he found himself running for re-election with the support of such Conservative bastions as Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid flagship, the Sun…

…Under Reagan, conservatives set about gutting the banking regulations instituted during the New Deal precisely to prevent a recurrence of the 1929 crash. Banks should be given maximum freedom to innovate, Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, believed. Bankers are smarter chaps than politicians and bureaucrats, and regulation was tyranny. Many of the same orthodoxies persisted through the Clinton era.

The crash of 2008 has been precisely a product of some of the exotic innovations by the clever chaps on Wall Street operating in a regulation-free environment, driven only by greed.

The victims of the Reagan legacy include millions of ordinary Americans who put their trust in institutions that encouraged them to invest their savings in a stock exchange whose growth had less to do with the real economy of manufacture and export, than with a series of speculative bubbles – first the internet, then real estate. The result was a kind of casino capitalism, in which stock prices had less to do with the ability of companies to deliver earnings, than with the belief that the values of the stock would rise due to demand from other buyers.

In today’s discourse, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is routinely viewed as the key indicator of the economy’s performance, but it reveals nothing of America’s crumbling infrastructure, the comprehensive de-industrialisation that has occurred since the end of the Cold War.

Never a particularly optimistic fellow, Davis warns that the damage is done; even the New Deal would not save us now. For one thing, the U.S. has lost its industrial base. For another, Davis makes the interesting point that the New Deal arose largely in response to the very real danger, in the 1930s, of American workers rallying to the Red Flag — it was the threat of revolution in response to the social collapse of the Depression that forced Washington to launch those massive public works programs building infrastructure, that got millions back on the job. And, of course, it really was the rearming of America for WWII that created full employment — an unlikely scenario now, given the way wars are fought and the way industry is structured to supply them.

A Theocracy of Dow-ism

I’m not an economist, but I was always rather puzzled by the manner in which the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and the stock market more generally, is taken in the mainstream U.S. media as the key indicator of the economy’s well-being. Not just in the media and the national conversation, but also in the habits of those running much of corporate America.

The Internet stock boom made clear that the stock market was not driven by the real potential earnings and profits of the companies whose equity was being traded; stocks were priced based on the assumption that their value would increase, less because of any clear business plan for profitability, than because of the expectation that in an environment of speculative frenzy, others would want to buy them. You know, like houses.

And even in the years of heady growth in the Dow, America’s economy was already deeply flawed:

- its industrial base denuded, shedding well paid union jobs that would propel people into the middle class and replacing them with poorly paid service sector jobs;

- its health system consuming close to one fifth of its GDP (by far the world’s highest share) but still leaving tens of millions of its citizens without adequate coverage — and prevented by the invoking of anticommunist demagoguery (invoked on behalf of those who profit most from the present system) from creating a national health system — even though the absence of such a system eventually forced such industrial giants as General Motors to relocate plants to Canada where the state health care system actually meant lower labor costs;

- its infrastructure crumbling amid an ideology that discouraged public-works investment;

- its citizenry discouraged from saving and encouraged to maintain dangerously high levels of household debt (mirroring that of the national economy, whose rampant consumption was financed by China’s savings) — President Bush’s first advice to Americans after 9/11 was to go shopping;

- its poorer citizens encouraged, under the rubric of the “ownership society”, to buy houses they couldn’t afford with mortgages they couldn’t afford, which were then bundled into financial instruments to repackaged as speculative investment vehicles;

- its savings, for retirment, or college, all directed towards the stock market, as if the only direction in which it could travel was up…

The Dow told of none of this, of course – except, perhaps, that the migration of the nation’s retirement savings into the equity markets will have inevitably helped inflate stock prices. But Americans were asked to believe that what was good for Goldman Sachs was good for them. Hell, Goldman-Sachs seems to be who you get in the Treasury no matter which party you vote for: The company’s former CEO, Bob Rubin, was Clinton’s Treasury Secretary (and currently advises Obama); Bush’s is Hank Paulson, another Goldman-Sachs alum.

As I wrote last weekend,

fixing the problems of the American economy will take some fundamental policy shifts, because it will require not only regulation of the banks but a programme to stimulate the economy not by cutting taxes, but by directing investment to infrastructure and the development of a new generation of industries. Wall Street is unlikely to be the source of the innovations required to turn around America’s economic decline.

To put this more bluntly, fixing America’s economy will require not only jettisoning the Reagan dogma of deregulation, shrinking government, and tax cuts as the cornucopia of economic growth, but also the Clinton legacy that turned the Democratic Party into as much of a friend to Wall Street as the Republicans had traditionally been. Wall Street is not the economy, and the last two decades have shown that the stock market can be hale and hearty even when the economy is being steadily denuded. It’s on fixing the real economy that voters should be forcing politicians to focus.

Shortly before I left my native Cape Town, South Africa, for New York in 1993, much of the city’s middle class was seized by a frenzy of greed organized into something called “The Aeroplane Game.” It was a simple pyramid scheme in which “passengers” were recruited, as $200 a pop, and when the bottom row of “seats” was filled, the “pilot” at the top of the pyramid took the $1600 of the newcomers, and everyone moved up a notch — as long as new “passengers” kept joining, everyone was assured of winning. But any fool not blinded by greed could see that sooner or later, there’d be hundreds or thousands of “passengers” left stranded on the tarmac. The game only worked as long as people could be persuaded to have confidence in the idea that the game could keep growing and growing, and that everyone would get rich. Mercifully, local law enforcement put a stop to it before too many people were burned.

Shortly before I left my native Cape Town, South Africa, for New York in 1993, much of the city’s middle class was seized by a frenzy of greed organized into something called “The Aeroplane Game.” It was a simple pyramid scheme in which “passengers” were recruited, as $200 a pop, and when the bottom row of “seats” was filled, the “pilot” at the top of the pyramid took the $1600 of the newcomers, and everyone moved up a notch — as long as new “passengers” kept joining, everyone was assured of winning. But any fool not blinded by greed could see that sooner or later, there’d be hundreds or thousands of “passengers” left stranded on the tarmac. The game only worked as long as people could be persuaded to have confidence in the idea that the game could keep growing and growing, and that everyone would get rich. Mercifully, local law enforcement put a stop to it before too many people were burned.